Still in the battle: an interview with Roger Craver

- Written by

- Joe Burnett

- Added

- April 20, 2017

Recently, friend of SOFII Craig Linton shared a great article by Nick Burne highlighting the amazing work the American Civil Liberties Union has been doing in response to the election of Donald Trump and his immediate attack on civil liberties for a number of groups, from Muslims to women to the LGBTQ+ community. We decided there could not be a better time to talk to The Agitator’s Roger Craver about this time of momentous protest and civic action. Roger is a legend in the American fundraising sector, having been a key figure in the civil rights movement of the sixties and seventies before founding the pioneering advocacy organisation Common Cause. In addition to regularly airing his wisdom and insights on The Agitator, Roger is still actively involved with ACLU, The Southern Poverty Law Center, the women’s rights movement as well as dedicating his considerable energies supporting a charity that helps survivors of torture and asylum seekers.

Given that rich, fascinating and unique background, we couldn’t wait to get his thoughts on what’s currently taking place across the USA and in fundraising in general.

Hi Roger! Could you please tell our readers a bit about your background in protest movements and activism?

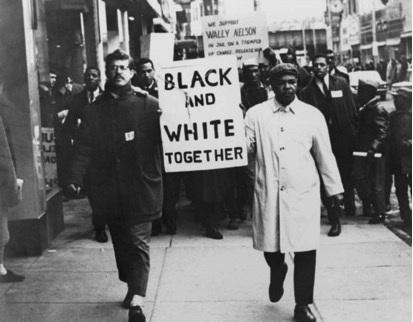

I started off in the civil rights movement in the late fifties and early sixties and from there went on to the anti-war movement in the late sixties after Dr King was assassinated. Then I went on to a fledgling organisation called Common Cause, which was the first advocacy organisation that accepted money in small amounts as opposed to being funded by the labour unions or by a small number of very wealthy individual donors. Common Cause was the first modern organisation to prove that you could attract tens of millions of dollars in small – $10, $15 – amounts.

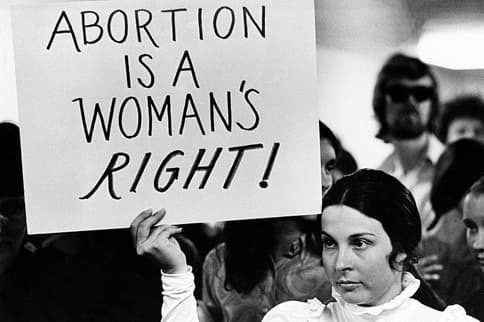

It was out of Common Cause that the example grew for the founding of organisations like the National Organization for Women, the Environmental Defense Fund, Greenpeace, all of which I helped to organise in the late sixties and early seventies. Most of my active career was spent building these types of citizen activist organisations and dealing with not only raising money but also the battles that occurred as a result, be it voting rights, fighting for equal pay, protection of the right to have an abortion, or conflicts of interest in government like the Watergate affair. So, yeah, a lot of years spent raising hell and trying to do something for human rights and human dignity. And I’m still doing it after 55 years – the battle keeps going. You don’t realise it when you’re young or a student, but these battles never stay won. Once you win a right there’s always going to be some son of a b**** who wants to take it away! That’s the evergreen aspect of this type of work.

How do you see the current upsurge in protests and campaigns? Is this a rebirth, reminiscent of the protest movements of the 1960s?

It’s both reminiscent and different. It’s reminiscent in that there’s a great deal of upset on the side of progressives or mainstream people in reaction not just to Trump’s victory but to his behaviour as well. People are pretty spooked. That’s reminiscent of the civil rights movement, when television showed African-Americans being beaten and having police dogs set on them, or children being bombed in churches. That was the early-to-mid sixties. It’s also reminiscent of the anti-Vietnam War protests of the late sixties and early seventies when people took to the streets, conducted teach-ins at universities. It’s finally reminiscent of the women’s rights movement, particularly around the issue of abortion and reproductive rights when, again, women took to the streets in defence of the right to choose.

Where it isn’t reminiscent is in the speed at which this has occurred, mainly because of social media. There was some concern that, although social media is powerful in terms of forming instant groups and getting people to take instant action at least electronically, the digital aspect might not translate into what is really essential for a lasting protest movement, which is on the ground activity. It seems to have translated quite well because, as you saw, the day after Trump’s inauguration we had the largest on the ground protest in the history of the nation, I think. Certainly in the history of Washington DC and it happened in dozens of cities across the United States, and also in Europe and Asia.

So it does seem that the grassroots have been activated by digital and, unlike what used to be called ‘slacktivism’, people signing a petition or doing something online only, it has a more lasting impact than we would have normally suspected. There are well-organised groups across a range of issues, from women’s rights to the Black Lives Matter folks to education reform to childcare to family leave: all of those issues that percolate below the surface have popped out and are gaining considerable constituencies and look like they will last for a longer period than the usual digital movements.

What do you think is so specific to Trump that people have become so galvanised? I acutely dislike the man, as I’m sure do many, but I don’t recall seeing such a level of activism when George W Bush, who was also very conservative, was president. Is it just down to Trump’s language and use of social media?

It’s a combination of things. It’s partly his language. Not so much his political incorrectness, because I think he probably wins points from various parts of the political spectrum for that, I think it’s his vulgarity and narcissism. It’s the belief on the part of those who oppose him that there’s no substance there, it’s all a charade. He will pick a topic and point of view in the moment for a rally or quick news soundbite, but he doesn’t have anything grounded in policy.

People are also fearful that Trump is accompanied by a US congress and a US senate, possibly even a judiciary, which are quite conservative and, therefore, offer foundation for some of the nonsense he spouts. So people are fearful that some of his crazy ideas that appeal to conservatives – and not all of his ideas do – may find a fertile seabed and take growth in the conservative congress. That’s the root of the political activism. People understand that healthcare, such as we have it in the United States, can be taken away pretty quickly, that women’s rights could be destroyed pretty quickly, that voting rights – which are already under threat – could be further harmed. There’s a feeling of urgency and impending doom that acts as the lubricant for this energy and action that we’re seeing in the country.

Do you think that lessons have been learned from previous protest movements, or even that there are any we need to take?

The lesson to be learned from all protest movements is that persistence and sustainability are required in an age of instant gratification and instant communication. As a general rule, people’s attention spans are not that great so the general worry for anyone who understands protest movements is sustainability. Can it last? People are remarkably unaware of history. These protest movements don’t produce instant results. For example, it took 144 years for women to win the right to vote in the United States! It took 90 years between the end of the Civil War and the right of African-Americans to vote. These movements have to be long-lived because making social change and political change in any culture is extraordinarily difficult. The big fear is that people will grow weary, or lose interest and move to the next shiny thing.

Now that doesn’t appear to be happening now, this latest resistance – as some call it – is getting stronger or at least maintaining strength. There aren’t many signs that people are abandoning [the movements], in fact there’s pretty good evidence that organisations like the ACLU are taking full advantage of the political climate and organising the people who have surfaced and beginning to train them. For example, the ACLU has mounted a training programme for this new wave of supporters and their existing members on what to do when the immigration authorities come calling, what to do if stopped by a cop or immigration officer, what to do about voting or reproductive rights, and so on. So there’s a lot of training happening at the grassroots level.

If nothing else, and I think there will be more to come, there will be hundreds of thousands of people who are more aware of their rights and how to protect them. The benefit has already been felt, and I suspect this is also occurring in Europe. In the UK, for example, people have a much better awareness of how government works. Now, this doesn’t mean that people are suddenly going to become students of history or civics, but it does mean – and you can see it in the increasing newspaper circulation figures here in the US and the emergence of new online media sites and podcasts dealing with civic life – that Trump is the spark that has ignited a far greater awareness about civil society and government than existed prior to this.

You sound really positive!

Oh I sound positive in the sense that there’s a resistance out there and it’s clear that the resistance will pay money to support its growth and cover the legal, technical and organisational expense of sustaining a movement. What isn’t clear is whether collectively these movements can make headway in parts of the country that we call the red states, which are fairly stuck in the past and afraid of globalisation. All for legitimate reasons, I don’t demean peoples’ fear. Just as you have millions of people in your former industrial regions who can’t find work, we have millions in the same situation in these red states. Unfortunately, they’re listening to politicians who say they can bring the work back, which they can’t. The work wasn’t lost just because of globalisation, it was lost because of automation, which is increasing with developments in artificial intelligence. The trends are really against the old industrial revolution model that the UK pioneered and the US perfected. Those days are over, but there isn’t really an acceptance by people that change has already occurred and we need to find a new model.

Unfortunately, the degree of intensity on both sides of the political spectrum is such that it makes working out a solution very, very difficult. We’re in a period of political name-calling and mean-spirited behaviour on both sides. Until we can somehow get to the middle, where these things are always resolved, it’s extraordinarily difficult. And that will take a long, long time, so we’re in for an extended period of turmoil. That’s why I raise the issue of whether these protest movements can sustain themselves for a long enough to become part of the political fabric. For example, can Bernie Sanders’ presidential campaign supporters be woven into office seekers and office holders at local, state and then even federal government level? Where do the politicians of the future come from? It’s a generation-long transition that we’re going through.

Tune in next week for the second part of our interview with Roger. To whet your appetite, here’s a selection of the questions we asked him:

Do you think it’s harder to make that transition when you come from the left and are potentially challenging the status quo?

How did the ACLU campaign start?

Do you think the internet facilitates or hinders transparency?

Do you think there are lessons in responsiveness to a crisis that could be learned from the current climate in the US? For example, the UK fundraising sector has yet to respond uniformly to its own crisis of nearly two years ago.

Is this a good time to be a campaigning fundraiser in the USA?