Ten fundraising truths inspired by Booker T. Washington

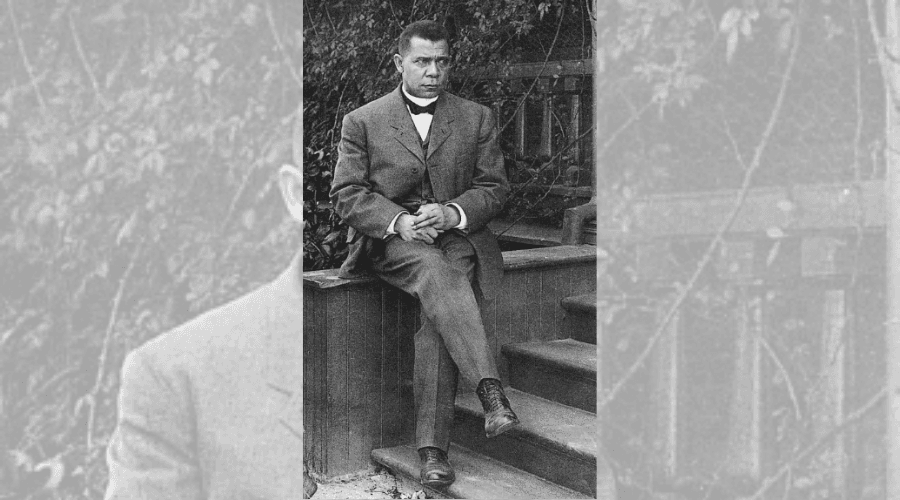

As fundraisers, we can learn so much from those who came before us. Booker T. Washington was the first president of the Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University). But did you know he was also a skilled fundraiser? In this article, Marina Jones shares ten fundraising truths based on Washington’s success and insight.

- Written by

- Marina Jones

- Added

- May 09, 2023

Booker T. (Taliaferro) Washington was born into slavery in 1856.

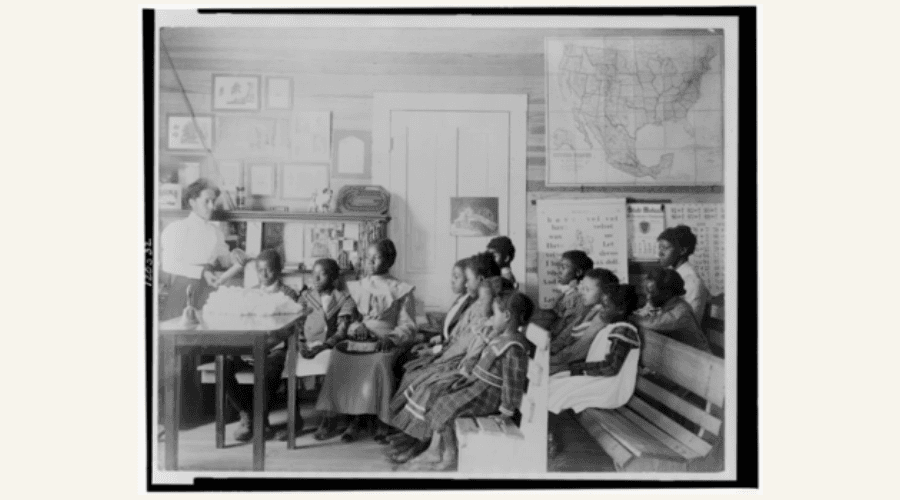

By 1881, aged just 25, he was named the leader of a new educational school, the Tuskegee Institute. Built on a former plantation site, students literally made bricks and farmed the land – all while completing their academic learning.

And the fundraising that was done for the school encompassed ‘all the usual suspects’ of a capital campaign. In fact, Washington once said:

‘The most of this money was obtained by holding festivals and concerts, and from small individual donations.’

Washington toured America making speeches to solicit funds and raise awareness of the needs of the school and his community. His 1901 autobiography Up from Slavery has a chapter entitled ‘Raising Funds’ – which reads like a modern fundraising how to guide in places. Considering it is 120 years old, it still has some useful lessons to teach us and reminders that fundraising was ever thus.

Let’s take a look at ten fundraising truths that I think we can draw from the life and ‘fundraising times’ of Booker T. Washington.

1) You don’t always get what you want (with the first ask)…

Ever been to a donor meeting and asked for support but come away with a small gift? Don’t worry you are in great company…

Washington went to meet Collis P. Huntington, seeking a large donation. Huntington had made his fortune on the railways and gave a bequest of his personal art collection worth US$3 million to the Metropolitan Art Museum. He also gave the proceeds of his Fifth Avenue mansion to Yale University (which he did not attend), as well as to other charities too.

Washington came away from this initial meeting with just two dollars. However, years later, he visited Huntingdon again and secured a US$50,000 gift. He said:

‘The first time I ever saw the late Collis P. Huntington, the great railroad man, he gave me two dollars for our school. The last time I saw him, which was a few months before he died, he gave me $50,000 toward our endowment fund.’

Like Washington, fundraisers today need to build trust and relationships with our donors before substantial gifts come in.

2) Fundraising is hard work...

Washington knew that fundraising is not easy. It requires grit and determination. It requires resilience and a demonstrable track record. You need to show donors the impact of your work, so they have the confidence in you to deliver what you promise.

When talking about his own fundraising for the Tuskegee Institute, Washington said:

‘Some people may say that it was Tuskegee’s good luck that brought to us this gift of $50,000. No, it was not luck. It was hard work. Nothing ever comes to one, that is worth having, except as a result of hard work.

When Mr. Huntington gave me the first two dollars, I did not blame him for not giving me more, but made up my mind that I was going to convince him by tangible results that we were worthy of larger gifts.

For a dozen years I made a strong effort to convince Mr. Huntington of the value of our work. I noted that just in proportion as the usefulness of the school grew, his donations increased.

Never did I meet an individual who took a more kindly and sympathetic interest in our school than did Mr. Huntington. He not only gave money to us, but took time in which to advise me, as a father would a son, about the general conduct of the school.’

3) We all know the fundraising maxim ‘Give, get or get off’ when applied to board members or development committees…

Over 100 years ago, Washington recounted one those ideal funders who both gave and but also got others inspired and giving:

‘Mr. Cleveland has not only shown his friendship for me in many personal ways, but has always consented to do anything I have asked of him for our school. This he has done, whether it was to make a personal donation or to use his influence in securing the donations of others.’

4) Use that anniversary to hook a campaign onto…

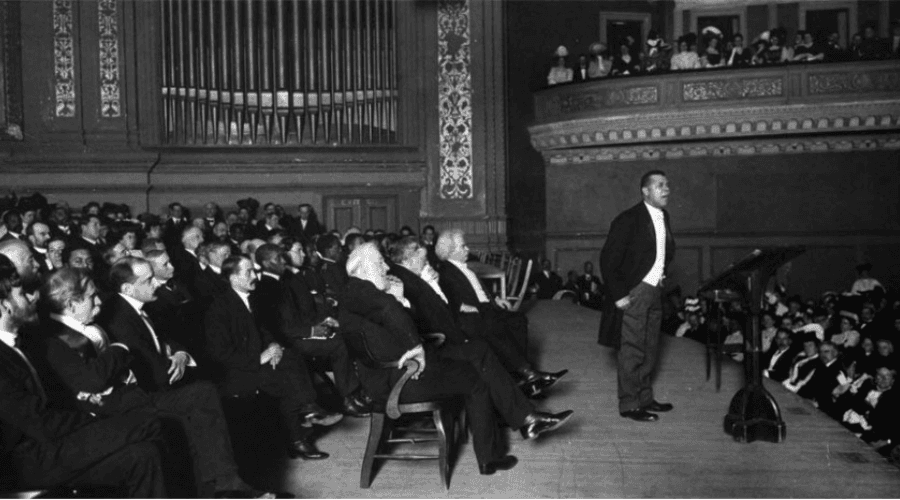

Washington made the most of an anniversary and used celebrity pulling power (who doesn’t) to launch a capital appeal in 1906. They celebrated the silver anniversary of the Tuskegee Institute at Carnegie Hall in New York. Speakers included Mark Twain and other famous orators of the day – Joseph Hodges Choate and Robert Curtis Ogden.

The campaign was ambitious, and according to The New York Times:

‘An added income of $90,000 a year was needed, an added endowment of $1,800,000 was essential, and a heating plant, to cost $34,000, was necessary.’

They already had an endowment fund of over US$1 million.

So, love them or hate them, anniversary campaigns and celebrities can be used to drum up publicity and support for a new campaign.

5) Don’t forget those nearest and dearest…

Often we forget to ask the beneficiaries themselves to give their time, treasure and talent to the charities that have made an impact on them. Washington instilled the need for funds and support in the graduates from the Tuskegee Institute who sent back regular donations ‘from twenty-five cents up to ten dollars’.

6) Respect the donor…

Throughout his autobiography there is a deep respect for the donor, the autonomy they have about how they spend their own money. Washington calls donors:

‘some of the best people in the world – to be more correct, I think I should say the best people in the world’

And he acknowledges their choice in making gifts where and when they choose:

‘that persons who possess sense enough to earn money have sense enough to know how to give it away’

When a donation doesn’t come or is smaller than we hoped, rather than a sense of entitlement to the money, he says (as quoted above in truth number two):

‘made up my mind that I was going to convince him by tangible results that we were worthy of larger gifts. For a dozen years I made a strong effort to convince Mr. Huntington of the value of our work’

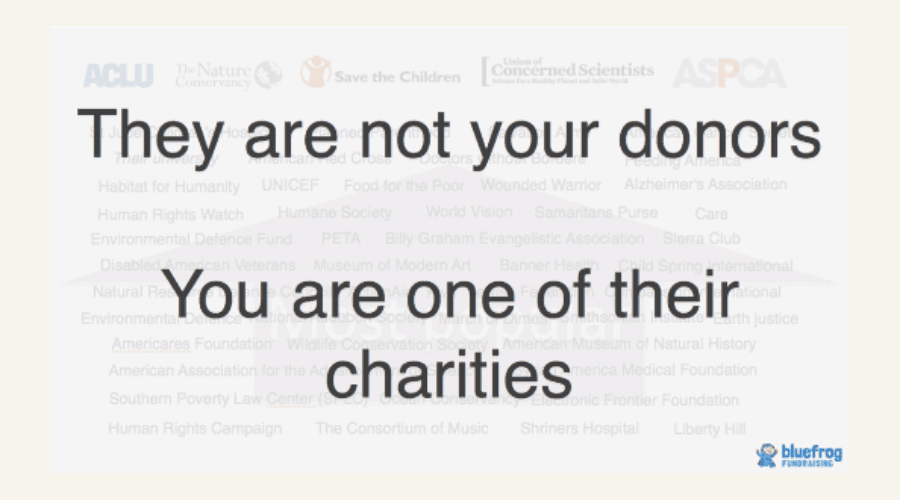

Washington’s words remind fundraisers that we need to respect our donors and their choices. We cannot not treat them as walking cash machines. As Mark Phillips says:

7) Fundraising is emotional and impacts on the fundraiser…

Washington describes going to visit a donor and walking two miles through a storm and being listened to but not getting a gift. He speaks of his frustration, ‘feeling that, in a measure, the three hours that I had spent in seeing him had been thrown away.’

Two years later he gets a cheque for US$10,000 and a legacy pledge!

Washington goes on to talk about what the gifts meant to him – and sometimes it is these harder earned gifts that can mean more:

‘I can hardly imagine any occurrence which could have given me more genuine satisfaction than the receipt of this draft. It was by far the largest single donation which up to that time the school had ever received.

It came at a time when an unusually long period had passed since we had received any money. We were in great distress because of lack of funds, and the nervous strain was tremendous.

It is difficult for me to think of any situation that is more trying on the nerves than that of conducting a large institution, with heavy financial obligations to meet, without knowing where the money is to come from to meet these obligations from month to month.’

Again, in his words we see that worrying about securing the funds needed to deliver your mission are often a concern. And that determination and resilience are needed.

8) Let the work speak for itself…

Like Washington says above, the value of the work ought to be what convinces, not pleading and begging:

‘the facts regarding the work… has been more effective than outright begging’

Show don’t tell – Washington arranged day trips for potential supporters and donors to see the work in action:

‘He [Booker T. Washington] announced that in April a special train would leave New York for Tuskegee and that the round-trip ticket would cost $50, covering all expenses.’

9) Build partnerships to succeed in raising more funds…

Washington worked to develop partnerships with philanthropists to ensure successful delivery of the programme through raising more money.

One of the most successful partnerships was with developed with Julius Rosenwald. This resulted in the establishment of the Rosenwald Foundation in 1917 and supported the building of schools across the South. It provided matching funds to communities that committed to operate the schools (the white school board) and for the construction and maintenance of schools to be matched by the local community.

US$4.4m of matched funding was secured, meaning nearly 5,000 new rural schools were built for black students throughout the South – most after Washington’s death in 1915. Rosenwald attached a sunset clause to his (US$70 million) foundation so all funds had to be spent by 1948.

10) Remember it is a joy and privilege for the donor to give and you, the fundraiser, are giving them that opportunity…

In his book, Washington talks about the joy that donors get from giving

‘an honour is conferred upon them in their being permitted to give… giving people who have money an opportunity to help’

He talks of getting letters from donors thanking him for the privilege of being able to help. One letter said:

‘I am so grateful to you Mr Washington for giving me the opportunity to help a good cause. It is a privilege to have a share in it.’

Washington describes fundraisers as ‘agents for doing their work’ – a reminder that as fundraisers we should not feel embarrassed or guilty about asking for money. We are giving those with resources the opportunity to help – we are their agents of good in the world.

I reckon if Booker T. Washington had used Twitter, he would have been a #ProudFundraiser.

IMAGES: © All images supplied by Marina Jones

Editor’s note: This blog and its images originally appeared on Marina’s website, and SOFII is very grateful to her for allowing us to reproduce it for you, here.