What can 6,000 appeal letters show you about fundraising 100 years ago?

In 1912, researcher William Harvey Allen studied an incredible 6,000 fundraising appeals – and then wrote a book about it. In some ways, it’s a bit like an early SOFII, a place where Allen documented the fundraising tips (and mistakes) of his time. Marina Jones takes you through his findings and shares some of the ways in which fundraising hasn’t changed.

- Written by

- Marina Jones

- Added

- July 13, 2023

In 1912, William Harvey Allen was the Director of the Bureau of Municipal Research and National Training School for Public Service in New York. He decided to examine 6,000 appeals that had been sent to a philanthropist, Mrs E H Harriman, asking for a whopping US$267,000,000 in charitable gifts.

After the death of her husband, who had been a railroad executive, Mrs Harriman became a noted and active philanthropist supporting a variety of causes. These are detailed in the book Modern Philanthropy A Study of Efficient Appealing and Giving.

But, to give a bit of context, in 1911 reports show that US$270,000,000 worth of donations were given in the United States of America (USA) of which US$30,635,647 was bequeathed to charity in wills.

Today, in this article, I will look at how a study of 6,000 100-year-old appeals can help us to answer the questions:

- What concerns of the time do we still care about?

- How advanced or not was fundraising?

- What guidance did they have for the writer of appeals, that we can apply to our fundraising today?

- Has much changed or have we always worried about the same issues and made the same mistakes?

Philanthropy, and what is deemed charitable, is always based in time, place and culture.

The vast majority of requests would still be deemed charitable today (health, disease, children, education) but there are a few more time specific ones – a national crusade against polygamy and celestial marriage (?!), home for aged Swedes and a museum of safety and sanitation.

So, what do the letters, and an analysis of them, show us about the concerns of the time that are still challenges for us today?

Finding where the money is most needed and deciding who ought to fund what

In 1912, there was a lack of interconnectivity between what charities and agencies existed, and who was helping who. There were not clear distinctions over whether something should be funded by the state or philanthropy, and debates about the role of both in trying to provide solutions.

The Bureau of Municipal Research often wrote back to petitioners with advice and guidance on the best place to get financial or practical help – for example, state provided support.

To provide greater efficiency about how decisions are made, the Bureau of Municipal Research suggested developing a central clearing house for the assessment of what was actually needed. This clearing house would be tasked with looking at duplications of provision, and signposting other appropriate services (both philanthropic and state). They wanted to create a directory of private philanthropy in each city to map what is provided and who is supporting each causal area.

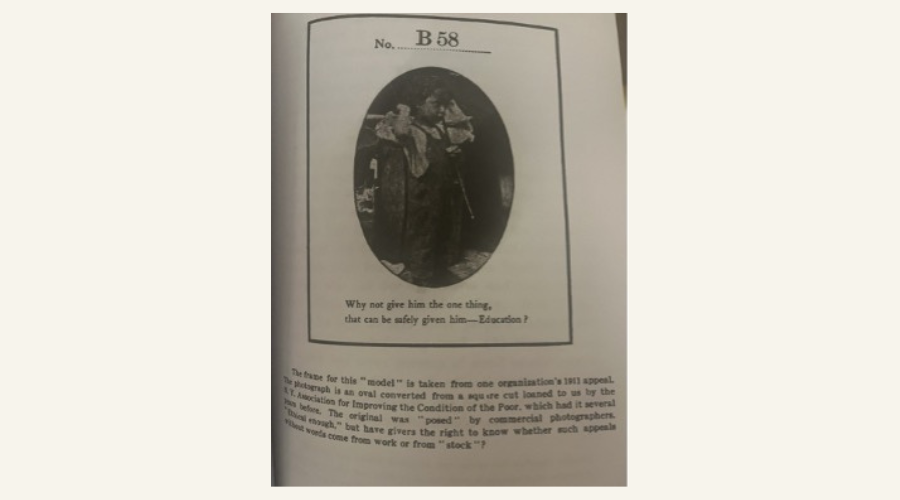

Questioning the ethics of images used in fundraising

Even in 1912 there were already concerns about the images used to generate sympathy and funds for good causes. The fact that the image below (for an appeal for the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor) was created in a photographer’s studio was questioned – as it does not show real beneficiaries or make clear that it is a created/staged image.

These concerns have been mirrored more recently with questions about how beneficiaries ought to be depicted in an ethical manner. Some charities have started using artificial intelligence (AI) to generate images for campaigns.

So, the debate about the best way to represent visually those that need support, continues to this day.

The challenge of core costs

It seems fundraisers have always shied away from talking about core costs – the cost of raising the funds and running the charity – as these quotes from William Harvey Allen demonstrate:

‘No appeals have stated what part of the gift would be used to pay for appealing.’

‘Few agencies keep a careful record of the postage, stationary and printing of appeals.’

Although the return on investment (ROI) on appeals seems not to be noted as standard in Allen’s research, it does cite that in 1910 the New York Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor spent US$1,500 on adverts in newspapers and got a return of US$11,500.

Worries about donor fatigue

Concerns about donor and compassion fatigue are not just current ones, as Allen also noted it as a concern in 1912:

‘Unfortunately for the starvation-broken-leg-blind-widow-with-five-children appeal, our nervous system requires ever increasing doses of sympathy drug, beyond the capacity of the English language or human suffering to supply.’

First do no harm

Allen said, ‘giving away money without wasting it and without harming anyone is pretty hard work.’

There was a real concern about how unthoughtful philanthropic activity could end up harming those it tried to help. They described this as ‘vagrant giving’ – as giving without thought or giving in the wrong way meant more harm was done.

Why are philanthropists motivated to give

Allen’s research also noted that:

‘The rich give for the same reason the near rich or the never rich give, because they like to or because they like it less than they dislike the alternatives presented’

‘If our appeals aim at motives we shall get more money than if we aim at their money:

1. Instinct – save a baby’s life

2. Comfort – Fresh air contribution before leaving for mountain or seashore

3. Commerce – give or advertise trade discounts to orphan asylums

4. Anti nuisance – Give to an importunate appealer for a day nursery

5. Anti slum – Free vaccination for slum babies

6. Pro slum – House to house nursing for the babies’ sake

7. Recognition of rights – 100 per cent of health protection for 100 per cent of babies, not as a gift but as their right.’

A century later Bekkers and Wiepking (2010) described eight major reasons why people donate to charity which are (1) awareness of need; (2) solicitation; (3) costs and benefits; (4) altruism; (5) reputation; (6) psychological benefits; (7) values; (8) efficacy.

We can see some overlap between the two lists of motivations but the older one does not have recognition of the role of the fundraiser, or that someone needs to make the ask.

Giving ought to be joyful and meaningful

Allen said, ‘those who give “without missing” are sure to miss it in their giving’.

He felt that too often in society circles they saw the ‘endless chain reaction’ of ‘give me US$25 today for my charity and tomorrow I will gladly give you US$25 for yours’. (With certain sets of donors has much changed?)

But he also noted that fundraisers had the opportunity to ‘delight [donors] in making others happy’.

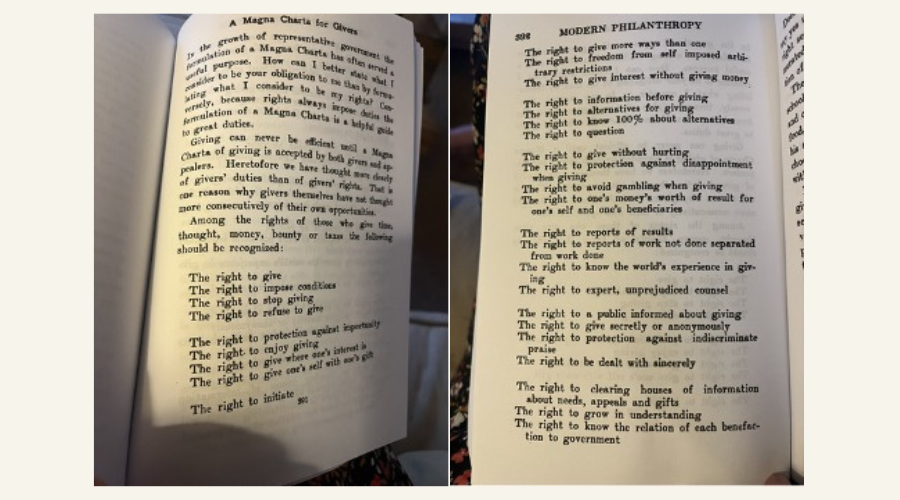

A charter for givers

William Harvey Allen proposed a ‘Magna Carter for Givers’ about how those that are asked ought to look and give, which he hoped would:

‘guarantee a sympathetic reading of letters’

‘organise and conduct a national museum that will do for the fields of efficient giving:

– the right to give

– the right to enjoy giving

– the right to reports of results

– the right to grow in understanding’

Role of charities in educating people about needs

Fundraising and the appeals we create do more than raise vitally needed funds, they help us as a society, to understand the challenges we face and why such conditions exist. Allen noted this too was true in 1912:

‘Appeals have done more to teach this country sociology than have all the universities.’

Introducing new trends – the first grant proposal form

In Allen’s book, Rockefeller is cited as introducing a new way of deciding on where funds are given – could this have been the first grant application form?

Allen said: ‘He gives all causes an equal chance by requesting that they be described briefly, unemotionally and by supportive facts in writing.’

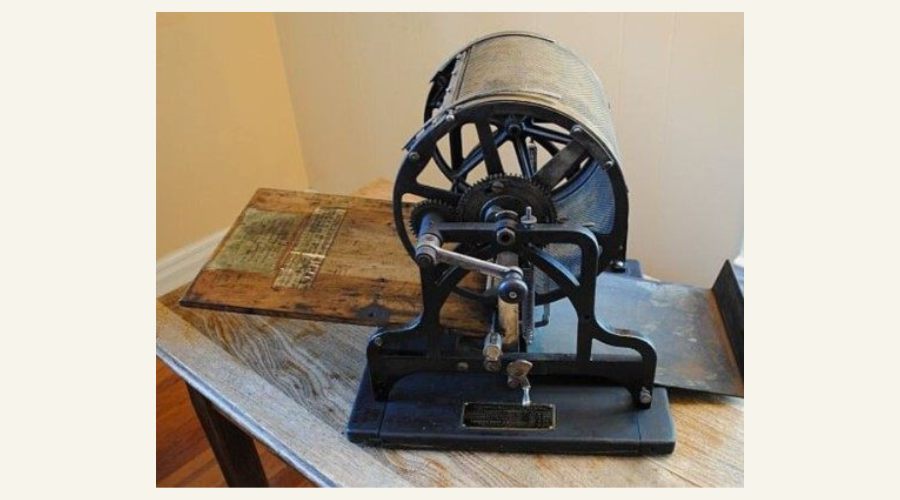

Embracing new technology

Fundraising always keeps up with new trends and embraces new technologies in its appeals.

The same was true in 1912. Allen noted, ‘like the largest and best organisations we have been compelled to adopt the mechanical follow up’.

The mimeograph was an early copying machine. These machines created multiple printed copies which were used to follow up original appeal letters. There were concerns that this lacked the personal touch, as letters would be hand addressed (Dear Mrs Harriman) with the rest a mimeograph.

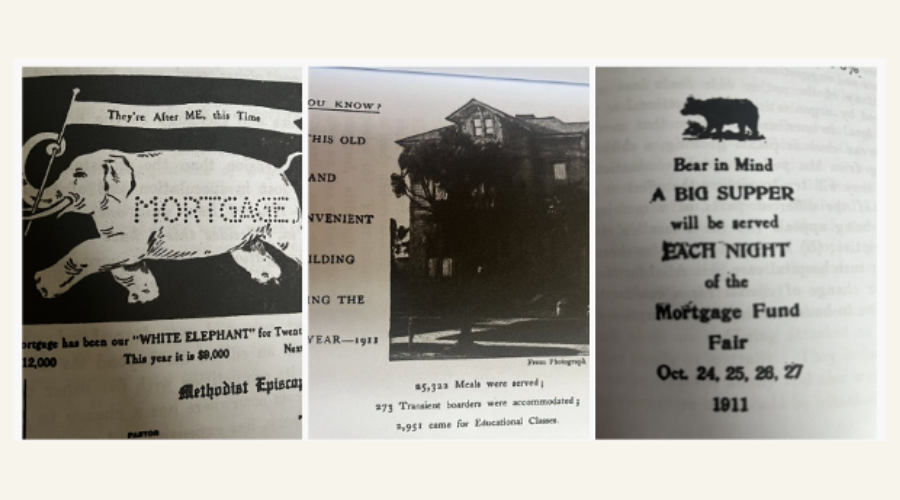

And finally, a few examples of charity adverts from 1911 and a few closing thoughts

Within the book Allen also included some press ads from the time:

Reading Modern Philanthropy A Study of Efficient Appealing and Giving was a fascinating insight into the state and concerns around fundraising from over one hundred years ago. I found it so interesting to see how little has changed and how we continue to have the same issues and debates. I hope you have enjoyed this trip through fundraising history too!

If you did, my next piece based on this fascinating study of 6,000 appeals will be appearing on SOFII soon. It looks at what we as fundraisers can learn from this vast number of appeals – more specifically when it comes to how we ask for money. Stay tuned!

IMAGES: © All images supplied by Marina Jones

Editor’s note: This blog and its images originally appeared on Marina’s website, and SOFII is very grateful to her for allowing us to reproduce it for you, here.