Legacy brochures from 90 years ago – what’s the same and what’s different to today?

SOFII is thrilled to bring you this rare ‘legacy edition’ from our ever-growing fundraising history project. Marina Jones has uncovered some gems in The Salvation Army archive, two legacy brochures from the 1930s. In this article she looks at what’s stayed the same (Marina found ten things!), as well as what’s changed, when it comes to talking to donors about making a gift in their will.

- Written by

- Marina Jones

- Added

- January 10, 2024

I recently visited the Salvation Army archives and I was excited to see there were two examples of legacy brochures from the 1930s on display. I was intrigued to find out what was included in them. I wanted to know; how did charities speak to their supporters about legacies?

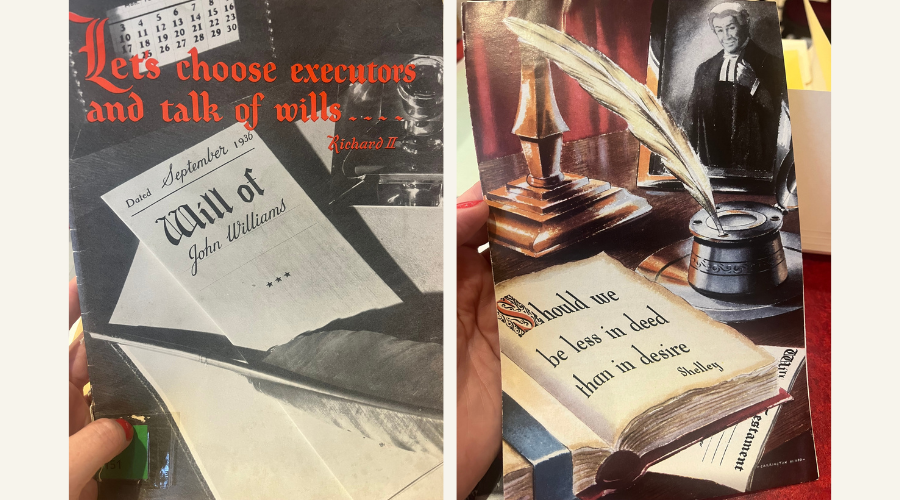

Let’s start by looking at the covers.

On the covers of the brochures, we have quotes from Shakespeare (above left) and Shelley (above right). This clearly speaks of a general knowledge of literature amongst The Salvation Army soldiers (even the Royal Shakespeare Company doesn’t quote William Shakespeare on their legacy page today!).

Having the date and the name of the person writing the will written by hand makes it feel personal, more authentic and a nudge to complete your own. The quill is poised ready for you to pick up and write your will. It is positioned in the correct place for a right-handed person (the majority of people) to start writing, making it easy for our brains to understand what is expected of us.

Wouldn’t it be great to test the impact of a personalised pack like this with the potential pledger’s name on the cover?

But that’s just the covers, I actually noticed a lot more interesting things when I started to read through the brochures and the information they had inside.

Ten things that were included – and what we would still include today

1. Case studies and examples of what a legacy has done in the past – this serves two purposes. First, it gives social proof that other people have done it and it is a normal thing for supporters to do. And secondly, it also gives an example of the impact a legacy can have.

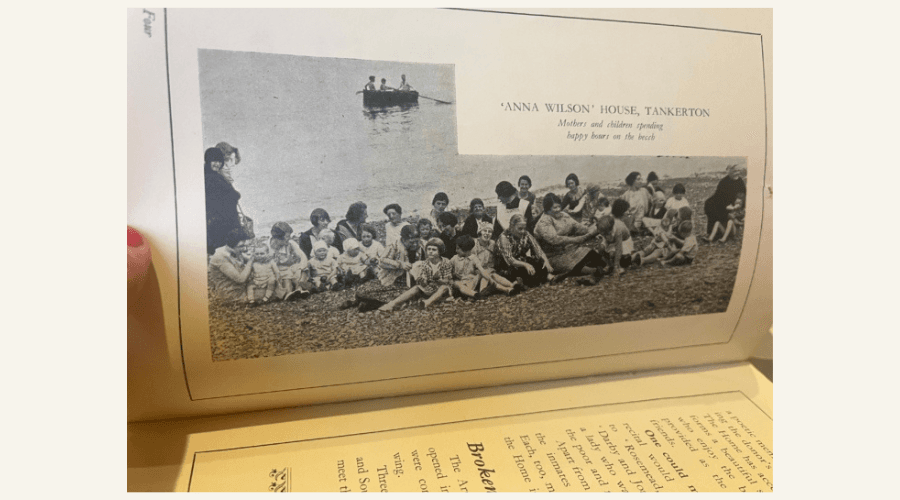

In the 1933 brochure, a case study details the Anna Wilson House which was established thanks to a woman’s legacy. It talks about the difference it made:

‘During the six years since then, more than four thousand women and children have enjoyed the hospitality of the Home and the benefits of a seaside holiday!’

It includes a picture of the women and children on the beach enjoying the experience (see below).

Today, legacy brochures continue to tell the story of the impact of legacy gifts and what they achieve for the charity.

2. List of legacies – There is a list of legacies received with the names and amounts of their bequests. This is a way of commemorating the donors and recording their names for posterity. It is also useful to demonstrate that this is a normal thing for The Salvation Army soldiers to do.

I am not sure we would list the amounts given nowadays. And the legacy donor credits would not be in the marketing brochure but on a wall, a plaque, a tree of life as leaves, a programme, a book of remembrance (physical or digital). Having a place where donors (and their families) know that they will be credited is an important addition.

3. The statement ‘we would advise you to consult your solicitor’ – this is similar to what we’d find now, as the fundraising team are not always legally trained, and a will ought to be executed by a professional solicitor.

In an 1893 issue of The Officer (The Salvation Army monthly magazine) there are detailed instructions about how to complete a legacy properly as there have been cases when the will has been insufficiently witnessed to be legally binding.

4. Statistics on impacts of the charity and its work – there are pages dedicated to the work of The Salvation Army, what it has achieved and the need for its work.

Clearly, back then (and now!) talking about the impact of your work is important.

5. Foreword by the current General – the General was the most senior figure in the organisation and wrote the foreword to the brochure.

Often, we use the most senior person in the organisation like the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) or Chair of the Board to be the authority figure talking about the vision and the need. They are someone well known to supporters, respected and trusted to enact the legacy gift.

6. The acknowledgement that talking about death is not easy – ‘It is a common mental attitude to think every one mortal but ourselves…. the very thought of making one’s Will, for instance is unwelcome to many people. They connect it with hastening, somehow, the inevitable dissolution’.

This links to terror management theory (which was only proposed as a formal theory in 2015). It says that reminders of our death kick in a self-preservation instinct that make us deny, delay or distract from any talk of death. This is one reason why people don’t have wills, as they cannot bring themselves to acknowledge and deal with their ultimate demise.

Not many legacy brochures now tend to be so up front in acknowledgment of this – they tend to focus on a celebration of life and looking back, looking forward and saying thank you.

During internal training and when getting organisational buy-in to promote legacy giving, this uncomfortableness does appear for some. However, people for whom death is more salient can be very up front about talking about funerals, death and legacies – it can be a self-imposed fear by fundraisers.

7. Choosing where your bequest goes – there are two forms that allow someone to make a gift to religious purposes or to the social work of The Salvation Army.

Many charities today allow the gift in your will to be directed to the area of the charity’s work that is most meaningful to you. Can you give the donors the autonomy to decide where their gift goes? Often, organisations try and keep the bequest wording as wide as possible as they don’t know where it will be most needed at the time of the realisation of the gift. But can you direct it to broad areas of work (like the religious purposes of social purposes) with a non-binding condition on it?

8. Keep drip feeding the message – The Salvation Army annual accounts statement of 1886 include the standard words for a bequest. It is important to get the information they need to enact their will. It is also important to drip feed the legacy message throughout communications with supporters as you never know when someone will be writing their will.

In fact, most of the time they are not writing their will so the regular drip feeding of the message means they might get the subtle nudge and reminder at the right moment and act on it.

Today a pledger might just need the registered charity number to take to their solicitor. But it is interesting to note that this predates this legal structure, and The Salvation Army’s bequest instruction read:

‘I give and bequeath unto William Booth, the General of the Salvation Army … or other General of the Army for the time being, his successor, the sum of …’

Today, consider where you can continue to talk about legacies and their impact – it may the annual accounts and reports (or this may be where you list and acknowledge the bequests received). Can you continue talking about legacies in newsletters and supporter magazines, as well as targeted correspondence and events?

9. Confidential correspondence – ‘General Booth will always … treat any communications made to him on the subject as strictly private and confidential.’

Making a will is a private affair and many people do not want to talk about the details of their will with other people. The assurance of a confidential communication about this is important for donors – and many charities toady continue to offer this confidentiality guarantee.

10. Named contact – when talking about something as important and personal as a will it is important to have a named person to speak to. The General, William Booth is listed as the contact for soldiers wishing to consider making this gift.

Giving a name, personal email and phone number (and sometimes even photo) of the person who you will talk to about a bequest can reassure donors (rather than an anonymous email address like, legacies@charityname.org).

Seven things that were different to how we do things in legacies nowadays

1. Suggesting the amount – The Salvation Army brochure lists amounts of bequests and what they would be endow in death (see image below).

Not many charities do this today – with rising costs of inflation it is hard to guarantee what a particular amount might do. Suggesting an amount could act as an anchor and make potential donors feel if they cannot give at that amount their gift would not be appreciated. The counter to that is that without any amount donors don’t know what a gift could do!

2. No pledger stories – while I didn’t see any in these historical brochures, recent research has shown that hearing from current pledgers who are alive and made a commitment to a gift in a will inspires us. We react to seeing people like us who have had similar experiences and connections to the charity making this commitment. Many legacy packs invite donors to share their story and memories.

3. No Contact form – today, we want donors to contact us and tell us that they have made a gift. So supporters are invited to get in touch with the charity and tell them they have left a gift (or even that they don’t and won’t and to stop asking).

4. No Legacy circles – there is no suggested ongoing contact with these pledgers in the 30s. There is no ‘let us thank you in your lifetime’. For some supporters this continued contact and acknowledgement is an important part of the gift and allows them to deepen their connection and meet other likeminded supporters.

5. No codicil or letter of wishes – donors now have greater flexibility and ability to add (or remove) you from their will!

6. The word ‘legacy’ – that’s right, legacy is the dominant word and phrasing here. The term gifts in wills is often preferred nowadays as the term bequest can sometimes be actively disliked by some donors.

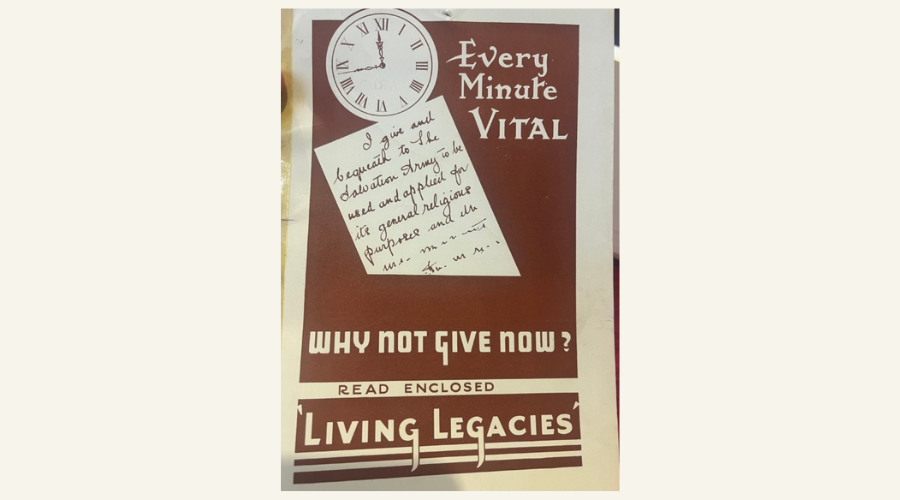

7. Living legacies – the 1933 brochure talks about living legacies. This seems to come in and out of fashion and is always a question for both the charity and the donor. When needs are so urgent and pressing it is best to have the money now? Is it best to give the money now and see the impact of the gift (and get thanked in your lifetime)? Or to wait until assets are realised on death and give then? With the climate emergency some donors are giving now to ensure that urgent action can take place.

As you can see below, the clock on the brochure is set at 11.45 emphasising the ‘every minute vital’ message, and that the clock is ticking. Often campaigns use the visual of a clock to reinforce the message that the time is running out to make a gift before a deadline. It acts as a powerful visual anchor.

And again, like the legacy brochures at the top, there is a handwritten note saying:

‘I bequeath and give to the Salvation Army to be used and applied for its general religious purposes and…’

There is something about the handwritten notes which helps the donor imagine themselves into the situation and that it could be their will.

So maybe not that much has changed in the last 90 years when it comes to asking for a legacy gift…

IMAGES: © All images supplied by Marina Jones

Editor’s note: This blog and its images originally appeared on Marina’s website, and SOFII is very grateful to her for allowing us to reproduce it for you, here.