What can 6,000 fundraising appeals from 1912 teach you about asking for money?

In part one of this series on William Harvey Allen’s review of 6,000 fundraising appeals, Marina Jones noted that the challenges fundraisers face hasn’t really changed much in 100+ years. But today, Marina looks at what these historical appeals can teach us about how we ask for money from donors. Dive in to discover ten key lessons.

- Written by

- Marina Jones

- Added

- July 20, 2023

‘Philanthropy’s mailbag has lessons of tremendous importance to the giver and not-yet-giver, to the individuals and organised appealer.’

In 1912, New York City-based William Harvey Allen, of the Bureau of Municipal Research, studied 6,000 appeal letters requesting a staggering US$267 million worth of assistance – from a philanthropist named Mrs Harriman.

His research aimed to draw out the best ways to make the ask, as well as some of the most common mistakes that fundraisers make while doing so. In fact, Allen believed there ‘is a need for a correspondence school in the art of appealing and the art of giving’.

He was right. And while the first fundraising guides might have been written by fourteenth century monks, we know it took many more decades to develop fundraising training via higher education courses, specialist training organisations and fundraising associations.

Today, as modern-day fundraisers, we know that many of the suggestions Allen makes from 1912 still ring true. Plus, they show that much of the same advice given to fundraisers has stayed the same for over a century!

So, without further ado – here are ten lessons (or reminders) about how you can create better fundraising appeals. All of them are inspired by William Harvey Allen’s extensive research of 1912.

1. Get the basics right

1a Name, address, spellings and actually ask for money

‘You misspelled her name, you addressed her at the wrong place, you misspelled a number of words which indicates carelessness.’ – William Harvey Allen

These are some of the mistakes listed in applications Allen reviewed:

- ‘(a) inserting intimate greeting as conclusion in an obviously circular letters; (b) failing to give any idea of the amount of money needed, or the nature of the work;

(c) writing for purposes known to have been adequately provided for’ - Letters claimed that beneficiary numbers were increasing when the accompanying annual report show numbers of those helped decreasing.

- Misspellings of Carnegie and Carbegie

- And budgets – the fundraisers asked for wild numbers with no back up of what was actually needed. When the Bureau of Municipal Research asked for clarification and details of what the money would be spent on, they could not account for the amount.

Allen knew, and we all know today, that paying attention to details and getting the basics right are incredibly important.

1b Appearances matter

How your appeal is presented is also important. You need to make it easy for your reader to read and understand what you are asking for.

Allen said, ‘The outward appearance of an appeal makes a greater difference than its actual importance justifies. Scrawly hand, blotted envelopes, crooked lines, lack of margins etc, establish a prejudice before the letter is opened... Of course, content may offset bias but readers of “begging letters” are only human and are willing to pay for a pleasant letterhead or a real appeal.’

1c Tailor the ask to your audience

Details matter and it is important to tailor your writing style to the person you are writing to. In 1912, William Harvey Allen said that writing the date as ‘Sept 8 1911’ implied a business correspondence (who knew?). However, ‘September eight Nineteen hundred and eleven’ implied a social correspondence.

He also felt that too many appeals used congratulations of publicly known news (birth of grandchild or death in the family) to make an excuse for correspondence – and this was viewed as disingenuous. Write for the audience of your appeal.

1d Length of the ask – the one page fetish

In the 6,000 applications the length of the ask ranged from a third of a page, all the way up to 19 pages. But Allen notes that ‘the points stand out clearly if the letter is brief and would appeal to class and the aesthetic taste’.

Allen said they ‘value[d] proposals for their brevity as well as the content’ but he had a particular horror of the ‘one page fetish’ when organisations or individuals tried to cram all the information onto one page. This means that the margins disappear, there are no headings, and the text is badly spaced (hands up if you have ever adjusted the margins to fit the proposal onto two sides of A4).

So please, make it easy for the reader to read and understand – William Harvey Allen suggests double or even triple spacing. And wide margins are appreciated by those reading your appeals.

2. Costly signalling – paper stock matters

When you choose to use the heavy paper weight with the embossed letter head you are giving your reader unconscious signals about your charity – its experience, budgets and ability to succeed.

This is known as ‘costly signal theory’ – demonstrating the value of the proposition, or the organisation. It can show that you are credible, successful and can afford to invest in good stationary.

In a restaurant, if you are given a menu on thicker paper stock (for paper fans 570 grams per square metre (gsm) vs 210 gsm) you will perceive the restaurant as more upscale and having given you better service.[i] The same is also true of the weight of cutlery!

There is often an internal debate about whether you ought to be seen to be spending money on appeals. Some may feel that 80gsm paper or light/cheap paper stock shows you are cost conscious and investing in the work rather than appeals. While others may say that good paper stock and a fancy donation pack and full colour letters demonstrates credibility and professional approach.

This is not a new discussion, and in 1912, William Harvey Allen felt it worked against the appealers/fundraisers:

‘Engraved letterheads are apt to drive away rich men who began their fortunes by small economies. A very neat type imitation of engraving however may produce a pleasant impression while still advertising economy.’

However, this might be a bias of the writer of the report. How people behave in the real world is often different to how they predict they will – and the subconscious cues that we get from the paper stock have an impact on how we react to appeals, and how much we give.

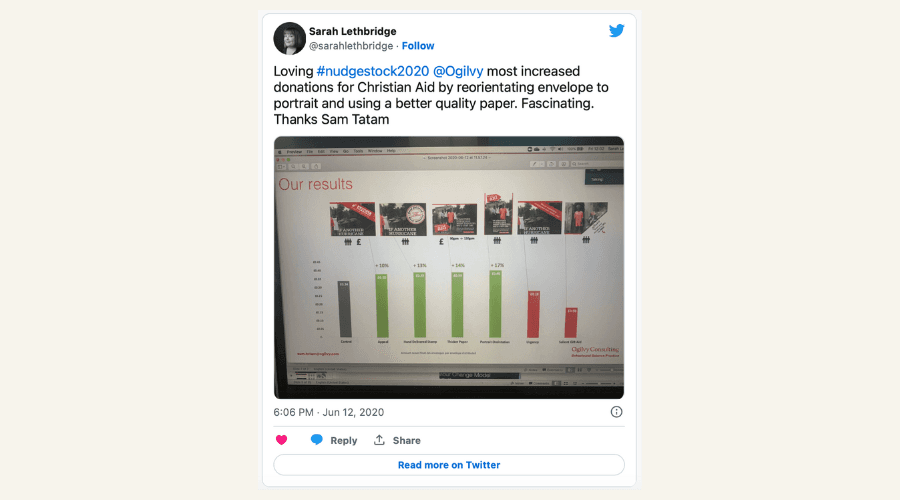

A decision science experiment run by Ogilvy with Christian Aid envelopes found that paper stock (90 gsm to 150 gsm) produced a higher average gift. You can read more about the different tests and surprising results in Change for Better.

3. Key ingredients of the case for support

William Harvey Allen offered ‘key ingredients of an effective statement of any cause’ which included:

- ‘summary to tell the story in a nutshell’

- cost

- making it about people not abstract concepts, ‘infants, not infancy, students not education’

- ‘show the differences’

4. Multiple (and effective) messengers

Like appeal packs today, the requests Allen studied came with what we now call ‘lift letters’ – with supporting statements and endorsements from bishops, other notable figures or institutions that could add credence to the appeal.

Who makes the ask and how likeable or how much authority they have on the subject have impacts our reactions – having multiple messengers can appeal to different sections of your supporters.

5. Make it more impactful by focussing on the one not the many

This is called the ‘identifiable victim effect’ and means our asks our more powerful if we focus our supporters onto one person that they can help. We can identify and see the impact of our gift on that individual – and once more people are added gifts decrease.

The ‘identifiable victim effect’ was not formally described until 1968, and its efficacy only proved in charitable appeals in the last twenty years. As fundraisers we often instinctively know what makes a powerful appeal, but the more recent evolutions in behavioural science unpack and explain why they work in our campaigns.

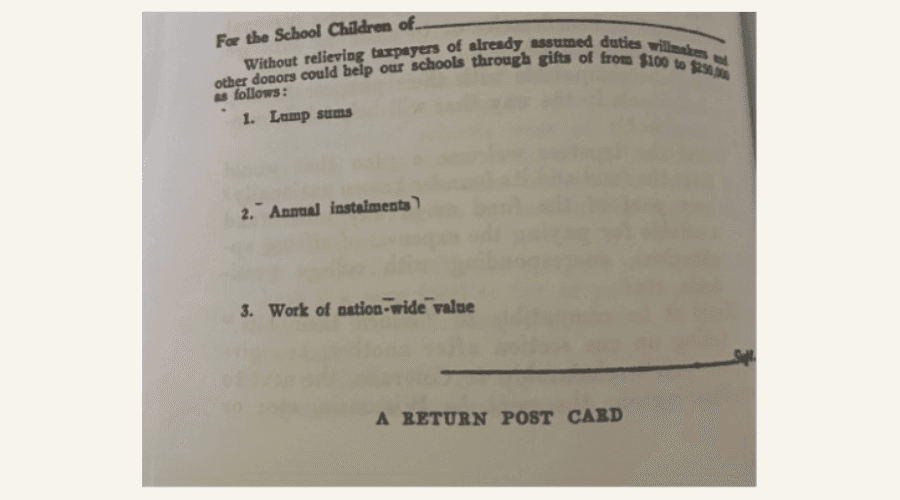

6. Make it easy to reply

Pre-printed reply postcards were used in the appeals to make it easier for people for people to reply and give them agency and options about how and where they wanted their gift to go.

7. Beware of overclaiming

Allen noted that lots of charities were claiming to be ‘the only’ one working in the field – rescuing girls from the street or rehoming boys. But Allen felt those making the decisions were aware of the diversity of offers and charities working in the field. These overclaims were described as ‘like cosmetics this rise seems to require putting on thicker and thicker in order to give the desired effect’.

8. How successful you ought to appear? Can being successful be a hindrance rather than a help?

Sometimes appearing too successful at solving the problem can work against grant seekers, William Harvey Allen notes:

‘And one turns away with the thought “I would like to help somebody that has some work still to be done”.’

But you must also show that you have a successful track record:

‘Pennies go to the hard luck story man but larger sums to for the man who seems either prosperous or on the road to prosperity.’

The challenge is you need to demonstrate your successful track record without alienating the giver.

9. Making contact with a potential donor – the spider’s web

How to reach the donors once you have identified them can be tricky. William Harvey Allen likens it to a spider’s web:

‘spider web philosophy is about different accesses – the secretary access, the family access, the lawyer access, the doctor access, the minister access, the news item access, the paid advertisement access, the social function access … butler access, lady’s maid access.’

We have all tried to map out how we can reach that potential donor – asking does someone on the board know them (how many of these spider web connections have you ever used? (Lawyer, doctor, family, staff, social, etc.) It was no different over a hundred years ago.

Although some of their methods seem a little more intense than ours, William Harvey Allen notes:

‘Agencies/organisations which notifies you of its intention to pursue you – in your mail, at your dinner parties and operas, on steamboats until you have made a contribution.’

10. Where we find new donors hasn’t changed

Nowadays we might look at annual reports or donor walls to see which philanthropists are active in a cause area. This was the same a century ago, as Allen noted:

‘we crib from each others list of contributors’

And finally…

Allen’s guidance shows that not much has changed about how we think about how to communicate with donors and make appeals for funds.

And finally, finally… fundraisers have always been charming and well informed:

‘So the woman who is expert in raising money for the poor Whites of the South is apt to be a woman whose personal charm and power of anecdote would be equally applicable or equally successful in discussing modern drama or the pilgrimages of Peter the Hermit.’ – William Harvey Allen

IMAGES: © All images supplied by Marina Jones

Editor’s note: This blog and its images originally appeared on Marina’s website, and SOFII is very grateful to her for allowing us to reproduce it for you, here.

[i] Maginini & Kim, 2016