The day World Vision welcomed me to their world

We’re always talking about tangible asks, tangible campaigns, tangible experiences. We talk to our donors about the impact they’ll be making and we talk about the difference they’re going to bring to the causes your charity exists to serve. In street fundraising, fundraisers have a split second to make someone stop and around five or 10 minutes to try and capture their emotions so that they want to support the charity’s cause. How easy is it to create something powerful, emotional, moving and above all tangible in street fundraising? I had a really great experience with a street fundraiser that I’d like to share with you all. It was so good that after becoming a donor, I went back and photographed the experience. I’ve never been a street fundraiser, but I guarantee there will be elements of this story that you can apply to your fundraising, whether you’re a fundraiser that sits in trusts, major donors, corporate, face to face, or direct mail.

- Written by

- Laura Croudace

- Added

- July 20, 2016

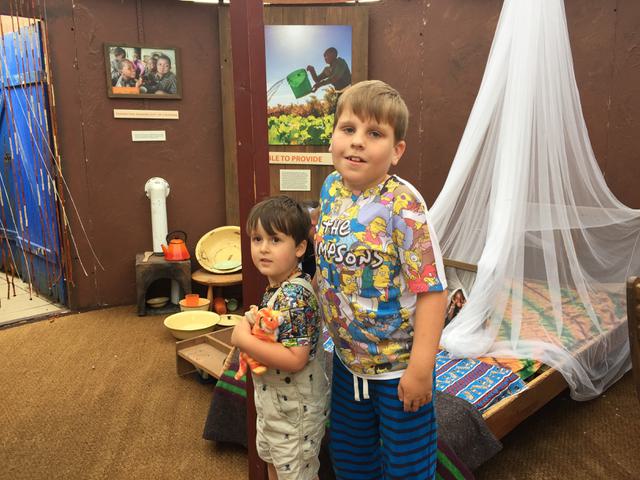

Last year I was walking through the car park on a sunny Saturday morning with my partner and two boys. We were heading into our local shopping centre to buy a birthday gift. There’s nothing extraordinary about that: until I spot a couple of mud huts in the distance and I wonder what they are.

When I approached, I noticed two signs on either side of the hut’s door that introduced me to Miatta, a woman around the same age as me, 29, with simple details about where she lives.

The fundraiser, Andre, who works for World Vision’s agency explained a little about Miatta and her family of five.

He then went on to ask us ‘how much money do Miatta's family earn in a entire year?’

My two boys, Opeie and Seth aged four and eight, said they weren’t sure. I guessed around about £3,000 a year. Andre asked the boys if they had an Xbox, and they said yes. Andre then explained that they earn on average £340 a year in total - the same price as an Xbox.

Andre then asked us, ‘Would you like to see where Miatta and her family live?’

Out of complete interest we went inside the hut.

On entering the mud hut the first thing we saw was a bed made from pallet style wood. It had a very thin mattress, which was dirty, and a small blanket placed on top. Andre explained that this was where the family of five slept at night. He asked us ‘Who do you think sleeps in the bed?’

As a mother, I automatically answered that it was the children.

Andre replied ‘No, the father sleeps here so he can get a good night’s rest, as he has to go out to work so the family have the £340 a year to live on.’

Behind the ‘bedroom area’ were a few bowls and a pile of branches. Andre explained, ‘Sadly, Miatta’s only son has died. There is nowhere for the fumes to go whilst cooking and at night the whole hut would fill up with smoke. This caused the boy to have worsening issues with his lungs. He developed pneumonia and couldn’t fight it off. The smoke made things a lot worse.'

Andre, then passed us each a bowl. My first thoughts were: how clever, they’re using coconut skins and other fruits to make their own bowls!

Andre then asked us, ‘What do you think happens when the children are ill and they’re eating from these bowls?’

I realised that yes, although it was clever to use hand-fashioned utensils, germs and bacteria could get into the grooves and cracks and thrive, spreading more disease – which instantly had my mind racing.

Next to the ‘bedroom area’ there was another display about the family's struggle to get water. Andre asked my boys, ‘How far do you think Miatta’s children, about the same age as you, have to walk before getting some water?’

None of us had any idea. Seth guessed a mile. My partner and I guessed around five miles.

Andre went on to explain that it was around five miles each way to collect water. Sometimes the children don’t manage it and drop the huge containers. They then have to go all the way back adding to their five hours’ long trip and preventing them going to school.

I asked about the quality of the water. Andre went on to explain that it doesn't come from a tap or a well, it's taken from a dirty stream.

We then took turns trying to lift the water container which weighed around 15kg.

We were then asked, ‘Would you like to see the difference World Vision made when we started to help Miatta and her family?’

Andre revealed through an African beaded curtain a much brighter space with small improvements that had a big impact on the family.

- A plastic corrugated roof to stop the rain getting in. This replaced the wooden/woven-leaf roof we had seen in the other hut. It was also a lot brighter.

- A chimney for the stove in the kitchen area so that the smoke from the fire can escape outside safely – preventing the deaths of children as they’re not inhaling it.

- Proper beds for the children and adults to sleep on with mosquito nets to prevent malaria.

- Metal cooking pots, bowls, kettles and plates so that germs don’t spread.

- A photograph explained that there is a well with clean water 10-minutes walk from Miatta’s house. This made a huge difference not only on the family's health, but the children's schooling as they no longer had to spend up to five hours a day collecting dirty water.

- Miatta’s children also had schoolbooks and a few toys to aid learning.

My boys really enjoyed seeing how other people live and how donating money can make a big difference to people’s lives. Seth, my eldest, particularly liked hearing about children the same age as him.

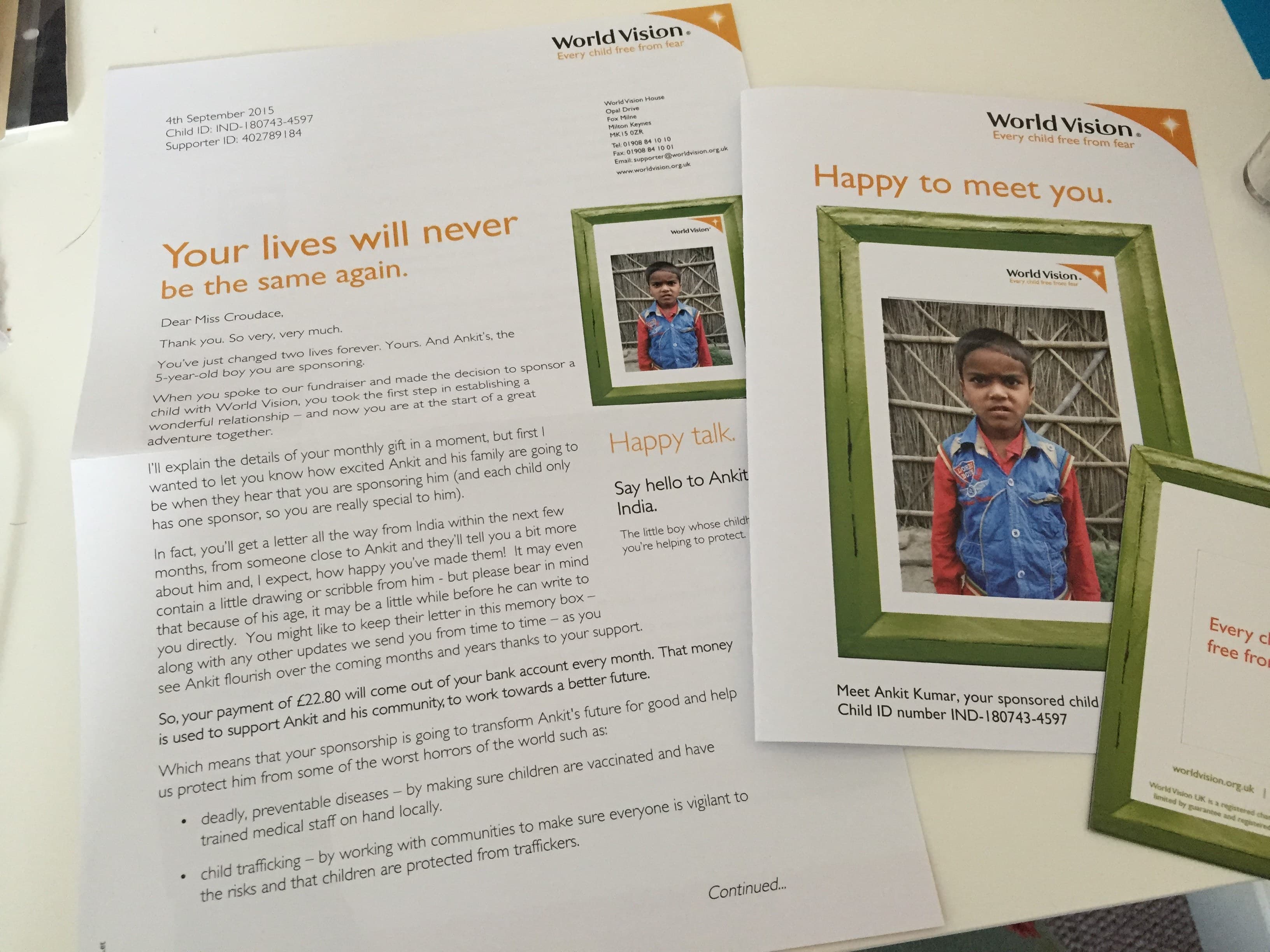

When it came to ‘the ask’ I asked Andre, how much it would cost to become a donor? And he asked me how much I thought it would cost per day to provide a child with clean water, nutritious food, healthcare, education and invest into their livelihood so they have a brighter future? My children and fiancée thought it was likely to be around £3 to £5. Now, being a UNICEF donor for the past 23 years, I knew it was probably between £0.70 and £0.80. Andre explained it was £0.75, about £22.80 a month, to look after a child.

Seth was really moved by what we had been talking about and decided he wanted to choose a child that wasn’t on the display board. He wanted to choose a little boy about four to eight years old in India. So Seth and I signed up.

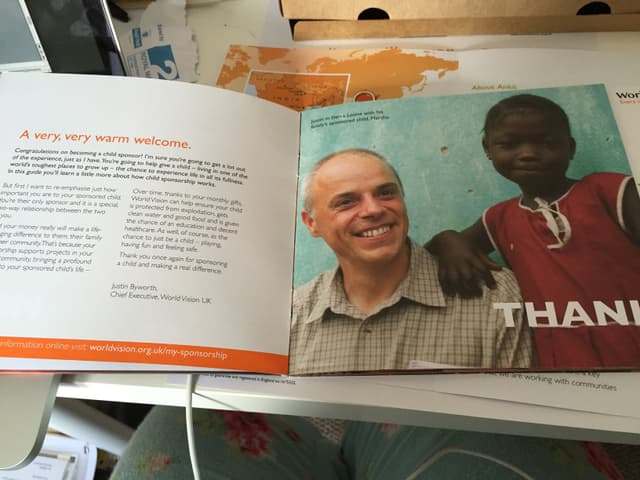

...Three weeks later this box dropped through our door. It tells us about the child we’re sponsoring and how to keep in touch with him.

Lessons to take away from this article:

- Ask the potential donor questions.

Rather than just reeling off a story, really make them think and emotionally engage them. You don’t have to say as much. Then, as the situation becomes far more relaxed, the person you’re speaking to will feel that it’s a two-way conversation, rather than the fundraiser just reciting information.

- Telling the story with simplicity and pace is powerful.

I can’t tell you about the number of street fundraisers who have come up to me and quoted bewildering statistics, figures and a list of problems. They're usually speaking so fast that they go slightly blue in the face! I just want to know how I’ll matter and how I’ll be helping someone. Tell the story slowly and create a less-is-more pitch.

- Show the actual impact.

Showing the difference your donor will be making is the magic sauce in the recipe. Think of creative ways to do this that are new and different.

- Make it as immersive and interactive.

This doesn’t just apply to face to face, elements of this would work well in a corporate pitch. As soon as I’d left the huts I started thinking about how I would want to get a smaller version of the huts to corporate pitches. The impact that interaction in pitches have on winning was demonstrated on a course I attended last year. And it works!

- Include some social proofing.

All of the great fundraisers like you are doing this. (Did you see what I did there?) One thing I really liked was that World Vision included a Polaroid wall of people who had donated in the local area. I found this to be very clever as the human brain is wired to want to fill in spaces and feel they’re part of something. A great book that discusses this is Happy Money by Elizabeth Dunn and Michael Norton (Oneworld Publications, UK , 2013).

The bits the fundraising managers, acquisition managers and agencies will want to read about.

- Cost of recruiting.

I asked Andre’s team leader how much it was going to cost World Vision to recruit me through the agency they were working for? He said it was around £150. So World Vision won’t see any benefit from my money until I’ve been donating for seven months. (That did make me feel quite disgruntled if I’m honest.)

- Why invest in face to face to recruit sponsors of children?

This is new and hasn’t been going for long. They explained that instead of investing in television they switched the budget to taking the huts around the UK as television had stopped working for World Vision.

- The ROI?

As it’s new there aren’t many figures on how well it’s doing. The team leader I spoke to explained that they were hitting all their targets and they had been told they were doing well.

What I’d like to know as a fundraiser:

- How do World Vision manage the logistics, sending out the right card, with the right child and the right information?

- How do they make it work financially? They have staff on the ground to pay. Do the children’s sponsorships cover that too?

- How do they find the children and collect the stories on a massive scale?

I’d also love to hear about your favourite street fundraising experiences. Tweet me at @alwayscolour