Communication and the English language

How staleness of imagery and lack of verbal precision hold fundraising back.

- Written by

- Ken Burnett

- Added

- February 11, 2021

While I’ve no wish to appear to younger fundraisers as an out-of-touch curmudgeon, I know that on this topic I risk being seen as clinging vainly to vanishing standards and outmoded ways against a rising, unstoppable tide of change.

But I’ll take the risk, because this is important. The problem I feel we all need to address transcends age, origin, gender and organisation. It applies to everyone, everywhere and has been a cause of concern longer than any of us has been alive. And for modern fundraisers, it’s seriously holding us back.

I’m talking about how people in our sector use words to convey meaning. Or, more precisely, how they don’t. Every day we all use words to communicate what we want to get across, in a range of ways. Our success or failure at it really matters. And mostly, most of us don’t manage to do it very well.

We have a choice when we sit down to write – to write something that might make a difference or to write something that will make no difference at all. We wouldn’t choose the latter deliberately, so our lack of success must be down to carelessness, or ignorance, or a failure to appreciate the importance of it.

Think about it a minute and you’ll see it’s a subject of some substance. We say lots, but convey little. We send out tons of information, but only a fraction of it gets through to achieve the ends we seek. Instead of communicating effectively we spray words and phrases around with seeming abandon, illuminating less and less.

Consider these fairly typical sentences from a recent draft case for support.

‘The fundraising appeal that is about to be launched will also provide our charity with an infrastructure that will boost on-going fundraising in order that the charity can continue to cover, post-appeal, what is hoped will be a diminishing shortfall in Government provision to the point where every needy child in the UK is receiving the support to which he or she is entitled. The appeal target is significant but, we believe, possible and this will be verified by our Feasibility Study. Please join our team and help us to ensure that affected children and young people have the confidence, support and independence to live the life they choose and deserve.’

Are you moved, inspired, or much the wiser? Me neither. Of course, it’s just a few lines out of context and regrettably I can’t share with you the entire document, though I doubt you’d want me to. Not because it says anything that’s outright wrong, rather because it takes so many words to convey so little that might engage or excite.

Yet words are precision instruments capable of taking our ideas and inspiration straight to the hearts and minds of our potential audiences. When assembled carefully and arranged in a certain way words have specific meaning evident for all. They convey exactly what we wish to convey. They marshal emotions, power and passion that will move mountains, allowing you, the writer, to affect and influence your reader precisely as you wish. Words matter. Why on earth do we allow them to be used so badly?

Just look at the written output from our organisations. Much if not most is missing its mark by miles, failing miserably to enter far less shift the perceptions and intentions of our targets.

Here are two more random examples of fundraising prose.

‘£3.00 a month helps us empower and build the capacity of local partner organisations to run locally-informed campaigns which create local, regional, national and international grass roots movements for political, economic and cultural change in a sustainable manner.

Networking and partnerships

We have become more effective at working with partner agencies to improve the services we offer. Our nascent work with Atmios should increase capacity in the RSE network in the Middle East and we are working with the Transforum Institute (a potential major funder) to increase capacity in Asia and Africa. It will continue to be important that we maintain the capacity to develop and sustain these relationships as a stronger RSE network is vital to our success.’

I’m sure someone will challenge me, exclaiming, ‘but that makes perfect sense to me!’ Yes, it might, but I worry whether it’ll make any sense to anyone else. Communication isn’t about talking to ourselves.

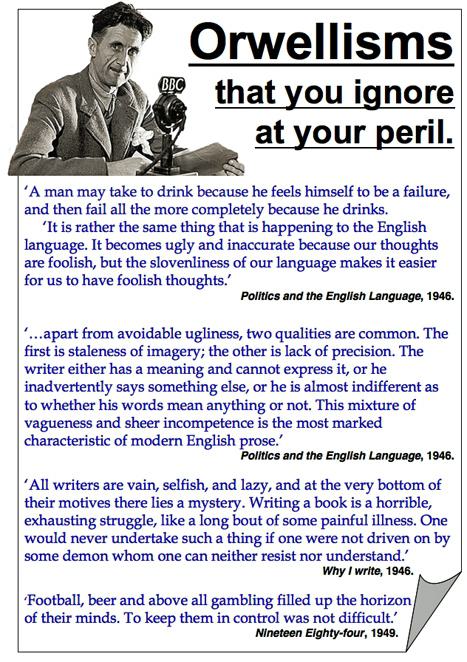

In 1946 George Orwell wrote his seminal essay Politics and the English Language. Its lessons are every bit as pertinent as they were back then, perhaps more so. Here in essence are his main points, somewhat paraphrased and wrapped around a few observations of my own.

- Words are precise tools worthy of careful deployment.

- Never waste a word. If a word or phrase does not add specific meaning, strike it out.

- Staleness of imagery and lack of precision are the twin enemies of clear thinking and effective communication.

- Sloppy writing not only denotes sloppy thinking, it fosters it.

- Bad writing habits are contagious. So are good ones.

- Read your copy out loud, to a trusted friend. Words have to sound right and if they don’t, at least one of you should notice.

- The decline in the use of language is reversible. People can teach themselves to write right. But, you have to work at it.

There’s a lot more in Orwell’s essay. I urge you to read it.

So, this is something we could change

As I read business reports I frequently feel I’m losing the will to live before I get halfway down page three. Reading the verbal output of fundraisers is too often mind numbing, even depressing. Perhaps the best way we and our organisations could change the world would be to first change the way we write about what we do. I’ve come to believe that if we’re to have real impact we must get better at telling our stories with power, passion, purpose and precision, so that we more surely move people to action.

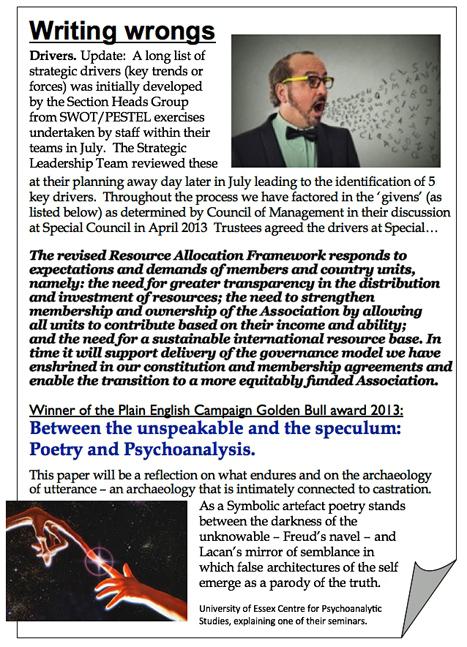

We all know jargon, gobbledegook and the overuse of acronyms when we see them, which is too often. The problem with most writing in our sector is that despite describing some of the most urgent needs and most moving stories in the world, so much of it is plain dull. Which is not easy to illustrate. And our tragedy is, so many people simply don’t see it.

It won’t get better until they do, until we collectively determine to root out dull, sloppy communication, with vigour. Meanwhile, if it wasn’t such a tired, over-used old cliché I’d be tempted to fret that when he reads charity communications, poor old Orwell must be turning in his grave.

An appreciation of the need for precision in language will stop you from writing something like, ‘Mummy, I’ve been feeling very socially excluded and marginalised lately,’ when what you really want your donors to appreciate is how it feels to be a teenager at the end of her tether. Or, it might cause you to resist saying ‘We’re preserving biodiversity’ when what you really mean is, ‘I don’t want to grow up in a world that has no sparrows.’

It was for good reason that Martin Luther King didn’t say, ‘I have a strategy, mission, vision, values and a rolling three-year plan’, but instead said simply, ‘I have a dream’. At the time few who listened to him had much idea of what that dream was but they got the gist of it and flocked to it, in no small part due to the language and imagery he used to draw them in.

© Ken Burnett 2021.

This article first appeared on Ken Burnett’s website in 2014. With thanks to Alan Clayton, George Smith, George Orwell and others for inspiration and phrases borrowed for this article. More from Ken Burnett can be found in SOFII’s Ken Burnett archive.