CDE project 6 section 4: bridging the empathy gap

From CDE project 6: the use and misuse of emotion, section 4.

- Written by

- Steven Dodds, Kate Woodford and Joel Du Bois

- Added

- March 16, 2017

Why do donors react so much more positively to victims of natural disaster than to victims of conflict?

By Steven Dodds, Kate Woodford and Joel Du Bois of The Harvest Strategy Partnership.

In this article commissioned specially for CDE’s emotion project, three experienced strategic thinkers challenge the accepted wisdom that victims of conflict will always be regarded as less deserving of donors’ support than the victims of natural disasters.

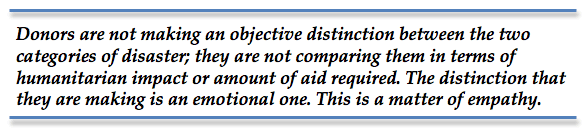

It is accepted wisdom that fundraising appeals for natural disasters raise more donations than those for conflicts. Although we cannot compare the two as equals, the discrepancy in response is striking. While the DEC’s most successful appeal for a natural disaster, the 2004 Boxing Day tsunami, raised a total of £392 million in six months, its most successful conflict appeal, running for 18 months for Syria in 2013 and 2014, raised £27 million. The pattern is reflected across all of the DEC’s appeals: natural disasters regularly raise many times more than conflicts, even though the number of people affected by conflict far outstrips those affected by natural disasters.

Why is this the case and what can we do to narrow this discrepancy? The question is an urgent one. The total number of people displaced by conflict and persecution in 2015 reached a staggering 65 million globally, four times as many as in 2005. In Syria alone, the death toll has risen to between 290,000 and 470,000, with more than 6.5 million people internally displaced and between 4 and 5 million people are now refugees. (The Boxing Day tsunami killed between 230,000 people and displaced 1.74 million.)

To understand the discrepancy in donor reaction we need to understand first of all that donors are not making an objective distinction between the two categories of disaster; they are not comparing them in terms of humanitarian impact or amount of aid required. The distinction that they are making is an emotional one. This is a matter of empathy and to tackle the problem we need to unpack the complex emotions of donors around the victims of conflict.

The empathy gap between donors and victims of conflict

While donors find it easy to empathise with victims of natural disaster, it is much more difficult for them to empathise with victims of conflict. Hearts go out instinctively to those trapped under buildings that collapse in earthquakes, or those taken unaware by floods. That could just as easily have been me, they think; I could have been standing on that beach. Indeed, the Boxing Day tsunami hit destinations popular with British tourists. But we find it much more difficult to put ourselves in the place of those in conflicts.

Fundraisers are well aware of this empathy gap between donors and victims of conflict and their response has been to produce communications that try to induce an emotional connection between the two – one strong enough and sharp enough to trigger a donation. The approach most often used today is to highlight the similarities between the donor’s and the victim’s worlds, or between the donor and victim themselves. Campaigns have transferred the Syrian conflict into a familiar British setting: Save The Children, ‘The Most Shocking Second a Day’, and UNICEF, ‘Unfairy Tales’, used familiar animation styles to tell the migration stories of Syrian children. Help Refugees underlined the immigrant backgrounds of British celebrities, ‘#Refugenes’.

As moving as any of these campaigns may have been, none of them have bridged the empathy gap in a lasting and sustainable way. The shock of identification with the victims of conflict lasts for a short while and fades quickly. Nowhere is this more obvious than with the image that dominated media coverage of the plight of refugees in September 2015, that of three-year-old Alan Kurdi lying dead on a beach in Turkey. Now, most commentators agree that this image was not the turning point in changing attitudes to the Syrian conflict that many had hoped.

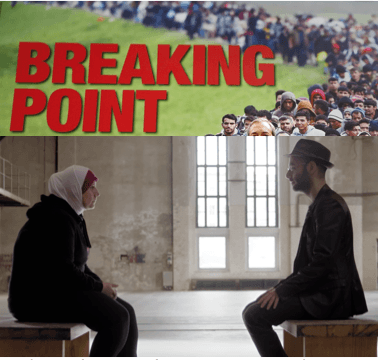

Indeed, it needs to be stressed that this is not simply a fundraising issue, but a broader political and social one. The stakes are huge. The failure not just of fundraising communications, but also of broader public discourse to bridge the empathy gap sustainably means that this space has been filled by those who would make it wider and deeper. Mainstream political opinion across Europe has shifted to capitalise on the perceived divide between ‘us’ and ‘them’; events such as Brexit have been brought about in considerable part by feeding negative emotions around victims of conflict.

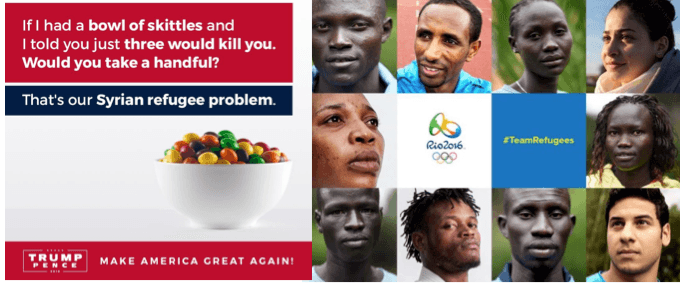

While negative approaches, such as UKIP's ‘breaking point’ poster aim to widen the empathy gap, reducing victims of conflict to an undistinguishable mass, positive approaches such as Amnesty International ‘Look Beyond Borders’ campaign attempt to create personal empathy between individual victims and non-victims – but do not directly address social fears.

Bridging the empathy gap is not simply a case of trying to demonstrate our shared humanity, or of putting a face and a story to those who are faceless and untold. It has to be noted that no such efforts are needed for the victims of natural disaster; we are not told the histories behind those in Aceh or Haiti before we donate to them. No, there are deeper, darker and more complex emotional forces at play. Comparing natural disasters and conflicts can help us to understand the nature of the empathy gap better.

When a natural disaster strikes, no human party is immediately to blame; in insurance terminology they are ‘acts of God’, events beyond human control. Human deficiencies can make them worse, such as poor school construction in Sichuan, but they don’t trigger the disaster in the first place. There is no doubt that the victims of a natural disaster are innocent, that something larger and completely out of their control was to blame. As a result, the gap between victim and donor is erased. Our shared innocence makes it easy to empathise with victims of natural disaster.

In a conflict, exactly the opposite emotional forces are in effect. Conflict is not perceived as a natural event, but one made by man. Conflict is political and brought about by human actors. While once, in the age of kings and empires, it could have been argued that the average person had no involvement in politics, today we in the Western world have been raised under the democratic ideal and taught that politics are shaped by the will of the people, that every one of us directly controls our political environment. We have been raised to see the relative peace of the last 70 years as a reflection of our own good governance, ‘democracy’ is equivalent to ‘peace’.

On a deep and unspoken level, we unconsciously hold those who live in countries that are in conflict – especially civil war, as in Syria – as responsible for their plight, even if indirectly. And this perceived blame makes it very difficult to empathise with them. For an example closer to home, immediately after the EU referendum in June 2016, reports of young people who had voted to remain falling out with parents, or friends, who had voted to leave demonstrate the same principle. The feeling of blame was strong enough to override personal relationships and empathy accrued over years, even if only for a short while.

Blame destroys empathy and creates divides. When the extra dimensions of religion and terrorism are added, as they are with the Syrian conflict, and where deep cultural conditioning that the Muslim world and the post-Christian Western world are polar opposites comes into play bridging this empathy gap has major hurdles to overcome: blame, fear and cultural incompatibility.

One sign of this is the number of campaigns and media communications that focus on children caught in the conflict. We perceive children as the only ones whose innate innocence absolves them of blame for their situation. Only children have successfully been portrayed as true victims of forces larger than they are. But on one level this is a shortcut, which avoids the difficulty of talking about non-child victims in an empathetic way. Shouldn’t fundraisers be asking themselves how they would produce an effective campaign focused on adult, able-bodied, responsible, educated women and men?

One final factor is that natural disasters are easy to understand, both in terms of cause and solution. They are perceived as being caused by a single trigger – a tectonic shift or monsoon rains – lasting for a measurable amount of time. In turn, the damage is seen as understandable and manageable, however vast it may be: it is ultimately perceived as a case of physical reconstruction. There is, therefore, a clear and straightforward objective for donations: to rebuild what was destroyed. This creates an immediate sense of relief and ability to help for the donor.

Conflicts, though, are wickedly complex. The conditions for conflict arise over a long time, are triggered by unpredictable events and are sustained by many different human actors. Resolving conflict is never simply a case of physical reconstruction. Emotionally, they are a source of worry and helplessness for donors.

If fundraising communication is going to bridge the empathy gap for a sustainable length of time, it needs to confront these emotional barriers, rather than avoiding or obscuring them. It needs to confront the unspoken blame that donors place on victims of conflict. It needs to counteract the fear of cultural divides between donors and victims. And it needs to alleviate the worry that the situation is simply too difficult to resolve and that we are all powerless in the face of it.

The empathy gap between donors and charities

Fundraisers have also to confront another uncomfortable truth: their troubled relationship with the giving public. For too long, charities have been waging their own war in their battle to raise ever more funds and convince ever more people to support their cause over another. When donors are reduced to little more than numbers – are seen as ‘targets’ in concerted and sustained ‘campaigns’ to yield the maximum return on investment – it is little wonder that the act of giving becomes an onerous one.

Even when donors have given generously and with great empathy, as in the case of Olive Cooke and countless other nameless kind-hearted folk, ignoring the emotional realities of supporters can have grave consequences. Emotionally unintelligent communications can make donors feel that their generosity is being exploited and even their trust betrayed.

Overlay that with the complexities of conflicts. Distant, endless wars that involve many protagonists inflicting, in the main, untold suffering and horrors on civilian populations that no three-minute news slot or direct mail letter can ever do adequate justice to. Add into the mix aid agencies that, despite their heroic efforts, are often presented in media coverage as little more than pawns for bigger political players. Confronted with all of this, giving £15 to send food and blankets to an earthquake zone becomes a whole lot less emotionally taxing for the average donor.

But how bad must it be to feel you can’t give? Are we putting donors in impossible situations, forcing them to choose which cause to support and which not? Is it fair that they have to decide what and who is more worthy of their support? We can’t assume that it is easy for naturally generous people to have to turn their backs on the victims of conflict. Don’t fundraisers have to ask themselves whether they are doing so because we’ve made it too hard for them to help?

War is a messy business and doesn’t fit the traditional fundraising model of problem–solution. There are no happy endings or quick fixes. Victims don’t live up to our ideal of the perfect before-and-after case study, they stare back at us from a world we don’t know or understand.

But by tiptoeing around the subject and feeding donors a diet of platitudes designed to smooth over the cracks we are ignoring the uncomfortable emotions we all have towards conflicts and their victims, we are skimming over the unpalatable truth about today’s wars and our collective complicity in them. So we end up simply pushing donors down an inevitable path – one of confusion and ultimately rejection.

Bridging the empathy gap

How can we overcome these deep-seated emotional gaps between donors, victims of conflict and fundraisers? We believe that fundraising communications so far have not confronted the deeper emotional reality of the empathy gap, instead trying to tackle it only on the surface. Bridging the gap is not simply a case of telling heart-warming or heart-breaking stories about individuals. It is not simply a case of putting a few faces in the public spotlight, whether Alan Kurdi or the Olympic refugee team. Emotionally intelligent fundraising for victims of conflict needs to tackle the deep-seated and uncomfortable emotions of the donor. It needs to resolve our unspoken blame, our fear, our frustrations and anxieties.

Although telling such an uncomfortably honest story may seem challenging both for donors and fundraisers, we believe there are both the appetite and the need for more emotionally informed strategies and communications regarding our relationship with victims of conflict.

While negative approaches such as the Trump campaign’s Skittles meme play on underlying fears around perceived risk, positive approaches such as the creation of the Olympic refugee team also focus on the exceptional, without highlighting the need to help all victims of conflict regardless of ability.

In recent months and years, as the tide of public discourse has turned in favour of closed borders and a general disengagement with international affairs, there has been an absence of an effective discourse for those who disagree with these views. The current British political system provides little succour for those with an appetite for greater international understanding, tolerance and support. There seems little doubt that many feel unrepresented and impotent, instead taking matters into their own hands as best they can, as witnessed by the popularity of volunteering or donating goods for refugees in the Calais Jungle, or the slacktivism that generated 4 million signatures for a second EU referendum.

It is perhaps the very size and anti-establishment nature of this vacuum that have so far prevented established aid agencies and humanitarian organisations from occupying it. Not only is the issue perceived as too large for any single organisation to deal with alone, it is also too important, both politically and personally, to be owned by any one charity.

Indeed, the empathy gap is also a power vacuum into which darker forces have been pulled. It is not difficult to understand how the messages of Nigel Farage, Marine Le Pen and Donald Trump have risen in popularity when there has been an absence of effective bridge-building messages that address the concerns of many. In other words, as one of the defining issues of our times, it is much bigger than ‘just’ fundraising and needs a correspondingly serious, committed response.

Bridging the empathy gap could therefore be more effectively achieved through a coalition of organisations jointly promoting a campaign or giving vehicle, which is shared by all but also separate from each. We believe that separating the issue from any individual organisation would create more distance for an honest, objective perspective of the problem and more space for donors to feel ownership themselves.

Whether aid agencies choose to co-ordinate their efforts or continue to approach the issue individually, stepping back and releasing their ownership could significantly reinvent and widen the appeal of communications. Currently it seems that humanitarian organisations, understandably pre-occupied with the scale and urgency of the issue, are gripping hold of it very tightly, unwilling to soften their grip for fear of losing it altogether. Paradoxically, it may be that letting go is what’s needed to allow more people to lend a hand.

Greater perspective and distance would enable aid agencies to speak more openly about our suspicions of culpability, making it clear that victims of conflict are not to blame for conflict. Casting the message in language that reflects democratic processes would allow us to draw parallels with recent situations in the UK that make clear the limits of personal impact on political outcomes, for instance those who voted for remain in the EU referendum, or who demonstrated in the Stop The War protest, ultimately did not prevent Brexit or the invasion of Iraq. Building a campaign around the concept of choice, votes, or grassroots activism could be a way to tackle the unspoken blame placed on victims of conflict. Personal stories of people who are in their predicament despite their best efforts could start to bridge the empathy gap: ‘I did not choose war. I was working for peace and democracy in Syria.’

A single co-ordinated campaign would also overcome the perceived enormity of the situation in terms of how to provide aid. We might even admit that aid agencies cannot do everything, and cannot stop the conflict, but that small, ongoing, concrete actions can make a huge difference. The campaign could be positioned as a continuing cause rather than as a crisis or emergency, starting to move fundraising efforts beyond the visceral, urgent and short term – helpful as this might be, especially for natural disasters – towards an approach which aims at sustained, longer-term giving and engagement.

Greater distance would also create space to open a discussion about the very real cultural differences between donors and victims of conflict, rather than trying to express our shared humanity. One could stress that we are different, but that doesn’t mean that victims of conflict are to be feared, or are any less deserving of support. Finding a platform that recognises these cultural differences while stressing our shared emotional motivations could be effective. Hope, for example, seems a particularly pertinent emotion to invoke, both for victims of conflict and for donors. Hope looks to the future with optimism but deals with the complex realities of the present; an expansive canvas for the world we want to live in, not the one that we do.

The suffering and upheaval faced by victims of conflict is an enormous and growing issue. We believe it is one for which our age will be remembered. But its scale has not been matched by the response from donors and fundraisers, nor indeed by any positive platform or public discourse. On the contrary, the empathy gap between donors and victims of conflict has been used only to spread messages that focus on our negative emotions, our suspicions and anxieties.

It is time that we change this. We need to bridge the empathy gap, by honestly admitting its existence and confronting the emotional and social conditions that create it. The goal is to create a platform that motivates donors to give as generously for victims of conflict as they do for victims of natural disaster, to provide support for millions of people suffering through no fault of their own. The task ahead is difficult, but emotionally intelligent communication can help us move forward in hope.

© Harvest Strategy Partnership 2016

About the Harvest Strategy Partnership (www.harvestagency.co.uk)

The Harvest Strategy Partnership works to solve deeply rooted challenges in the fundraising world. A collaborative initiative bringing together a network of independent specialists since 2012, Harvest’s clients include Amnesty International, Barnardo’s, RSPCA and the International Committee of the Red Cross.