CDE project 19 summary: evidence of impact and effectiveness

- Written by

- The Commission on the Donor Experience

- Added

- May 01, 2017

How to demonstrate the difference made by donors’ generosity

Ben Russell and Susan Pinkney, April 2017

Reviewed by: David Gold

Summary

Giving to charity is an opportunity to do something worthwhile with your money and an opportunity to make a difference. Every donor’s most pressing question is ‘Will my gift be valued; will it make a difference?’. A donation is much, much more than a transaction. It is a gift borne out of concern for a cause, people’s human desire to help achieve a charity’s aims and the desire to help the people that charity supports.

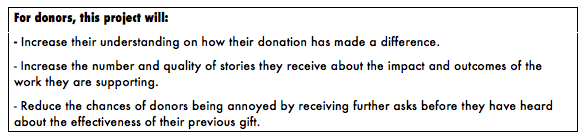

This project will look at how charities can start building relationships with their supporters by communicating their successes, achievements and impact. It will look at what donors would like to see and how charities can show donors that their money makes a difference.

Including information about charities’ work—their outputs, achievements and outcomes—can be a useful part of communications to donors. That does not mean being prescriptive about how we measure or describe our success, achievements and impact. Nor does it mean replacing other messages about the need for help, problems in the world and potential solutions.

It does mean responding to the apparent interest among donors to know more. Executives and trustees rightly feel responsible for maximising the funds available for delivering their charitable objectives. Faced with challenging targets and often armed with a highly sophisticated understanding of what motivates donors to give, fundraisers may rely on messaging that focuses on the need for more funds at the expense of redress for funds received. Leaders must weigh rising demand for impact evidence with immediate funding goals to ensure donors have the information they feel is needed to build a positive, long-term relationship with the charities they support.

We looked at evidence of what charity supporters would like to hear from the charities they support, and we carried our own polling to inform fundraisers and communicators. As well as asking what people would like, we also asked practical questions about how people would like to receive information and whether they were happy with the volume of communications they receive, which we hope will help charities get the balance right for their supporters.

After all, whenever someone receives a gift, it is only natural to say ‘thank you’, and it is only natural to say how a gift has made a difference to you.

Actions to consider:

- Include some content about your achievements in follow-up messages to donors. This may seem obvious, but it is crucial. Donors say they are interested in finding out more about what charities do and the difference they make. Other research shows that simple, human-scale and individual stories cut through, particularly when citing the voices of service users. Polling and focus group research finds that people express high levels of interest in finding out more about the impact of charities and the work they do. This represents an opportunity to connect with donors, build a relationship with them and take them on a journey. The desire for this kind of information is amplified amongst younger donors, where there is a real thirst for this type of information. This suggests that charities should test stories about their impact as an integral part of their wider communications to donors.

- Talk about more than the ask. Some people tend to express irritation if they are asked for more after giving—although we do know that many people do give nonetheless. Some express the feeling that fundraising asks outweigh information about achievements. Of course, charities need to ask, but telling stories about work and achievements can help thank donors and build positive relationships.

- Easily understood, compelling and human stories of how charities help are likely to cut through. People claim they would like to hear about who the charity helps, the overall impact of donations and how the charity helps. This chimes with experimental research that suggests simple human examples are the most effective, although it may be worth backing them up with the bigger picture.

- People say they prefer easily controlled communications. When asked, email is clearly the means of communication that people prefer, followed by newsletters. See CDE project 13 – Giving donors choices and managing preferences.

- Most people say they are satisfied with the level of communications they receive. More communications is not necessarily needed. When asked, most people say the amount of communications they receive from the charities they support is about right. The key issue is to ensure that communications build positive relationships to support further engagement in the future.

- Test as you go. Social experiments demonstrate that just showing an effectiveness score can be ineffective or negative. So mix up stories about your work and its outcomes with other approaches.

Key points:

- There are many ways to show your successes and achievements. It is important to be clear about your objectives and how you are helping your supporters be part of that success. Everyone wants to be part of a success. People like to feel a sense of achievement; supporting charities and building a relationship with them can be a great way of doing that. The impact a charity makes on its beneficiaries is all part of that success. Of course, there is much debate about how to measure impact in charities. Measures range from simple feedback about people who have been helped or statistics about charities’ activities to sophisticated metrics and social return on investment measures. Feedback on actions and results are useful. More detailed models can provide valuable evidence for sophisticated funders, information for evaluating work and be a good source of raw materials for telling a charity’s story to different audiences.

- Talking about impact can have negative consequences, so testing is important. Claimed and actual behaviour can often be quite different. Some experimental studies show that talking about impact in the wrong way can have little, or even negative, effect on people. It is very important to test messages and learn from experience.

- The differences between what donors say about impact and how they act does not diminish the need to communicate impact. Some may conclude that because claimed and actual behaviour are not the same, polling of donor opinions can be ignored. However, the difference in stated preference and action points to a risk that must be averted. Demand for greater transparency on effectiveness is likely to grow and, unless we are able to incrementally change donor responses to information on impact through improved communication, donor trust may fall.

- Assessing and communicating impact can make organisations more effective at delivering their charitable objectives. Measuring and communicating success and impact is about more than soliciting donations. We live in a world where people increasingly expect organisations to be accountable to stakeholder scrutiny. This trend cannot be ignored and early adopters will likely reap rewards in the long run. However, those rewards are not limited to fundraising. Impact measurement and transparency challenge organisations to improve, can reveal waste and lead to innovation.

- Communicating impact really matters. The report clearly

stresses that donors want to know more about the impact of their gifts, successes, achievements and any shortcomings that may be encountered. Donors want to see outcomes rather details. They are more interested in evidence of achievement than organisational information. So, fundraisers should work to satisfy the apparent interest among donors to know more and to have that information presented in the right way for them.- Feedback on the impact of each gift is essential.

- It is no good waiting weeks to get back to a donor with that feedback.

- In a celebratory way, fundraisers should frequently remind donors of the difference they make.

- That feedback should be very good indeed.

- The charity sector should aspire to be famous for great feedback. Ken Burnett puts it like this: ‘Fundraisers should aspire to the 5 Fs – to be famous for frequent, fast, fabulous feedback.’

- Get the balance right. Whenever someone receives a gift, it is only natural to say ‘thank you’, and it is only natural to say how a gift has made a difference to you. The project urges charities to get the balance right and show fundraisers how to do it. See CDE project 4 – Thank you and welcome.

- Include everyone in your feedback. One in five donors complain that they do not hear from a charity after they have given a gift. Always say ‘thank you’ and always give a gift. Recognize too that another one in five donors would prefer not to hear from you again. So offer those donors a clear and easy way to make further communication choices, including a full opt-out if that is what they wish. See CDE project 13 – Giving donors choices and managing preferences.

- Develop appropriate metrics. Focusing on overheads or fundraising costs creates a perverse incentive for charities to avoid investment, risk and innovation. (Can the authors enlarge on the consequences and remedy for this?). EG. Charities must, therefore, put more attention into explaining how they work and why.

- Telling our stories better. Public perceptions of charity impact are far worse than the realities. Essential expenditure on activities, such as admin and fundraising, are also lower than the public believes. There are good stories here.

- Do not always ask for money. Many people feel that the fear of being inundated with requests for more money prevents them from giving. There is a tension between the desire to know more and worry that a donation will lead to many requests for more money, which donors identify as a real barrier to giving. So, with your feedback, provide reassurance that the donor’s gift is always appreciated.

- Understand your donors. Even when charities believe they are telling a story about what they do, they also are asking for money. The donor may focus solely on the latter. So, present your stories with this in mind.

- Provide easy to grasp examples. Donors are unlikely to have conducted research before donating, so good examples of achievements will be particularly important at the start of your relationship.

- Mitigate ‘annoyance’ and ‘awkwardness’. These are words donors use to express how they feel when asked for money.

- Take care with language and how you use emotion. See CDE project 1 – The use and misuse of language for guidance on the complex subject of language and CDE project 6 - The use and misuse of emotion.

- Recognise that charity communications are not just about reporting on fundraising impact. They also build trust and relationships, educate people about the cause, provide information and advice, and directly impact the cause itself.