Investing in testing — part 1

Why would you spend a big chunk of a slender budget with no immediate prospect of return?

- Written by

- Ken Burnett

- Added

- April 23, 2012

View original image

View original image

On my first day as a fundraiser I quickly spotted I had a huge problem. My target to recruit 5,000 new donors had been accepted by my predecessor and the board so was set in stone. But our acquisition cost then was running a lot higher than expected, at £24+ per signed-up supporter (bear with me, this was a while ago, though if anything the lessons are even more valid today). And my donor acquisition budget was fixed at £60,000.

You do the maths. We were doomed to underachieve.

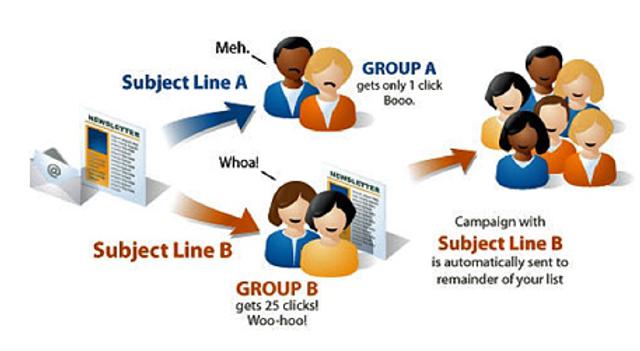

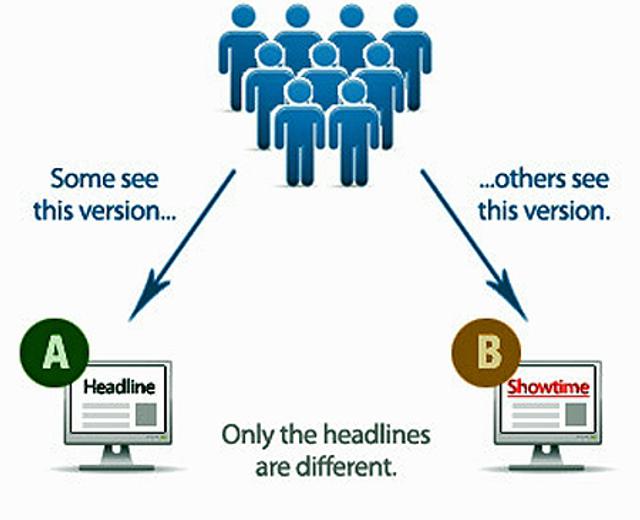

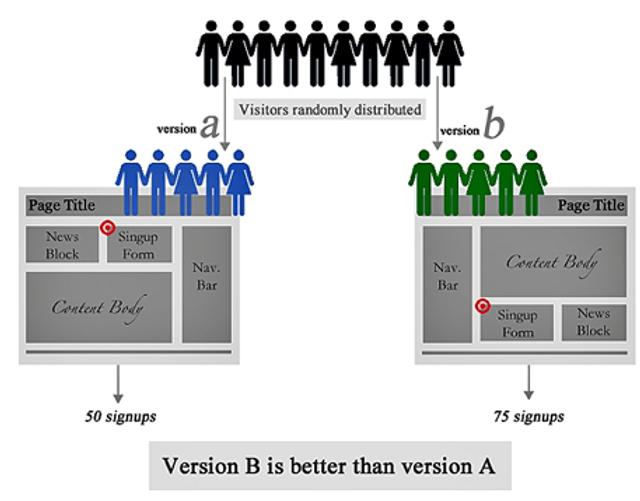

To make things worse my guiding trustee and mentor Harold Sumption* told me that in his (considerable) experience I really should set aside ten per cent of this already patently inadequate acquisition budget for, you’ve guessed it, testing. And he said that we shouldn’t target for any returns from this money. We should be prepared to squander it all on a structured series of split tests.

View original image

View original image

Crikey! And I’d been warned that I should ignore Harold’s advice at my peril. But why in the name of sanity would a career-concerned fundraiser decide to spend £6,000 of his wholly inadequate stipend on something as vaguely unproductive and time-consuming as testing? Well, here’s a clue: we went on to smash our 5,000 donor target and drove down acquisition cost by several hundred percent. In quick succession we developed new media, new creative treatments and new formats. We broke the mould not just of our own fundraising but of the then current direct marketing paradigm. Our charity grew, and prospered.

I wrote generally about this theme a while back when I described the delights and indispensability of something called ‘the guard book’. A well-maintained guard book system is essential for any properly maintained test programme. But it isn’t its raison d’être. Rather, if you don’t test properly, your prospects for innovation are reduced to a matter of random chance. Your results therefore will be unlikely to improve and will more likely decline. If you do test properly you may expend time and energy following some blind alleys, but before long you’ll find a new way of doing things and your fundraising will prosper. You may have to kiss a few frogs first, but you will find your prince.

View original image

View original image

I’ve long suspected that the regime of rigorous testing that used to pervade in every seriously ambitious charity has in many organisations been allowed to slip, with expensive and at times near terminal consequences. It is almost entirely absent in organisations running face-to-face and telephone fundraising campaigns because they are so often afflicted with the ‘lowest possible acquisition cost’ mentality. This is the fault not of the commercial suppliers but of their short-sighted clients.

So I was somewhat encouraged (deliberate understatement here) to learn that my friends at specialist telephone agency R Fundraising have decided to actively encourage all their clients to commit to a programme of sustained and rigorous testing and improvement. Long overdue in their sector, if you ask me. Worth emulating if you’re not one of their clients.

Amanda Oates was R Fundraising’s inspirationally-named director of evidence and learning – how many of those do you know? And can we have more please? At a recent client seminar at the Inch Hotel she told me a bit about how they see testing.

‘It’s an ongoing process,‘ says Amanda. ‘We work with our clients to constantly improve and refine the key variables of their acquisition and development campaigns, including strategy, timing, creative and story-telling. We don’t use scripts, instead we encourage our people to have real conversations built on rapport. But we can still test a variety of different approaches.’

Here are eight of the key things she’s learned.

- Test first what’s likely to make most difference.

- Only test one thing at a time.

- Keep it simple.

- Record everything rigorously.

- Note external factors, eg time of year, weather, etc.

- Define concisely your conclusion from each test.

- If the difference is marginal, test again.

- Test across different media to check results and build learning.

Sound advice. In the 1970s and 80s (yes, it was some years ago, but I still feel good when I think about it) the charity I worked for, ActionAid, became quite famous as the UK’s fastest-growing charity. It was also known, not inaccurately, as Britain’s first completely direct-marketed charity. But really it should have been known as Britain’s most thorough testing charity – the one that invested in testing. Because that’s what we were best at. It was Harold Sumption’s wisdom, not mine. I just learned from what he decreed.

It’s advice that R Fundraising seems to be following now. Their lucky clients will benefit heaps, I’m sure.

Fundraising, however you do it, will not get easier, cheaper, or less competitive. Holding on to whatever edge you have is bound to get harder. So testing rises like a beacon here, saying follow me if you would find the light. It really is a no-brainer (hateful phrase, but it says what it is).

Something else I learned early was to listen to the legendary David Ogilvy (see SOFII). As Ogilvy once pointed out, the difference between a good surgeon (he might have said fundraiser, or whatever) and a great surgeon is simply that the great surgeon knows more. Testing ensures that you know more. As such, it outperforms most other investments you could make – even donor acquisition.

Those with ears will hear.

© Ken Burnett 2012

Final notes

*Amongst numerous achievements Harold Sumption was the architect of Oxfam’s transformational press advertising in the 1950s and 60s (see SOFII here). He went on to found the world-famous International Fundraising Congress, held each year in Holland. He was worth listening to.