The use and misuse of emotion part one

Why fundraisers should study emotions and learn to use them better.

- Written by

- Ken Burnett

- Added

- September 01, 2019

I recently presented a sold-out session for the Institute of Fundraising on the theme of The use and misuse of emotion. Midway through preparing it I decided to broaden the scope into a rant about the negative image our publics generally have of we fundraisers. I fear this derives largely from how poorly so many fundraisers communicate their emotion-laden causes to their emotionally receptive audiences. We’re missing a massive opportunity.

After my presentation a young man came up to me. I’ve known him some years through emails and via social media, but we’d never met. I observed it was good to finally meet. He said, ‘Yes, especially as at the start of my career as a schools fundraiser you told me an emotional story that shaped my attitude to fundraising.’ He then described a passage from a book I wrote in 1992, in which I’d said, ‘don’t go into schools asking the children to raise money, instead inspire them and teach them to be really interested in and to care about your cause. Thus empowered, they’ll eagerly go out and raise money because, they’ll instantly get, that’s the best way they can help.’

This, he said, he’d found to be good advice. I’d all but forgotten it, though the core point, as it happens, had been the focus of the second part of my presentation. Depressingly, fundraisers seem to think they must constantly, continually ask for money, which might go some way to explaining the public’s distaste for fundraisers. Instead they’d be better advised to communicate differently, to focus more on the life-changing differences donors make and the good feelings that they get when you tell them, in the right way, about the things they make possible. There’s truth in the phrase, ‘You don’t get if you don’t ask’. But you don’t have to bludgeon people with asking when it’s patently obvious every charity wants donations. If you’re always asking for money donors and prospective donors will cross the street to avoid you, or hang up, or bin your appeal. And – which is fatal for fundraising – they’ll come to dislike you, because what you’re doing is not very nice.

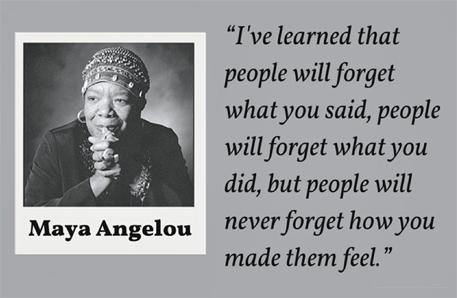

Maya Angelou’s famous quote is now so well worn it’s almost a cliché. It should be a guiding beacon for fundraisers. We all (well, all except those whose childhood missed the best of Disney magic) remember how we felt when Bambi’s mother died. This oh-so-emotional fragment of cinematic history apparently introduced successive generations of tiny children to the concept of their parents’ mortality – what an awesome responsibility, whether for a cause or a cartoon company.

We all know giving is rarely rational. So fundraising is inevitably emotional. Thus you’d think we’d study emotional fundraising scrupulously and do our best to ensure that fundraisers everywhere are steeped in a deep understanding of it. Not so. After 43 years as a professional fundraiser I’m only just beginning to grapple with a basic understanding of emotions. Yet I spent much of 2016 and 2017 immersed in the subject, compiling Project 6 for the Commission on the Donor Experience. You can find their 40+ feature articles from 26 expert contributors and a host of other instructive examples here, on SOFII – a quick, accessible, summary immersion in this complex, evolving subject.

I remember once a trustee board of serious scientists and academics from a famous international cancer charity telling me how difficult it is to interest people in cancer research. ‘It’s so complex and progress is so slow’, they said, ‘people can’t get their heads around it. Research,’ they continued, ‘is painstaking, gradual, technical, even dull, people in gloomy lab coats in dismal portacabins surrounded by the bewildering, inhibiting paraphernalia of science, working seemingly endlessly on complicated problems beyond the comprehension of 99 per cent of donors. Donors can’t possibly be interested.’

‘Yes,’ I replied, ‘undeniably cancer research is about all those things. Though it’s also not really about any of them. What it’s about is me and my loved ones. It’s about some of the most daunting, testing events in our family life. Research is about hope, it’s about small steps that make big differences – I don’t need to understand them to care passionately about those steps. Cancer research is about me and my family getting to spend more time together, with the people we love.’

Both are true, but they are fundamentally different. Why do fundraisers so often fail to appreciate the difference, when they apply their craft?

I submit it’s because fundraisers don’t study emotions sufficiently, many don’t give the subject even scant consideration, far less recognise its central importance to their work. So we misuse emotion as often as we use it well and mostly we miss opportunities to tell our stories as well as we might. Which explains why donors, I’ve found, are so often fearful of emotion from fundraisers and don’t trust us to manage our emotional messages well.

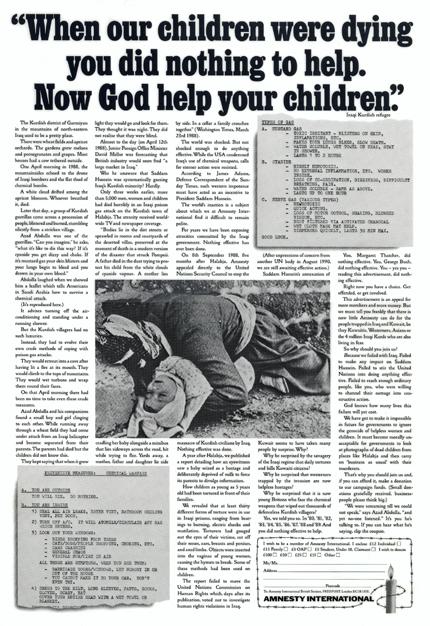

If fundraisers were truly committed to maximising their income by mastering their use of emotions they’d study this hugely complex subject much more closely. At the very least they’d be comprehensively steeped in the best examples of emotional communication. They’d be familiar with the huge body of tested work that forms the core of their craft and the epitome of their art. Evidently they’re not, despite the easy availability of many detailed, well-documented examples of the best of emotional fundraising (free 24/7 on SOFII and elsewhere). Two worth linking here are Make-a-Wish Canada’s masterly direct mail acquisition letter and Amnesty International UK section’s series of press ads that shook a nation. These are recognised worldwide as instructive, all-too-rare examples of the emotional copywriter’s craft and art. They consistently repay detailed study. But, sadly, far too many fundraisers simply don’t give them that.

Even more unlikely these days is that charities will commission original world-class emotional campaigns such as Amnesty’s, above. Far too many charities, to their great cost, simply don’t know how to work with the creative talent capable of originating such effective, impactful emotional fundraising. To their cost most charities don’t have the first clue of how to organise or manage the environment in which such great work can flourish.

The study of emotions is still evolving, still relatively unexplored. But it’s not new. So there’s no excuse for fundraisers failing to take it seriously and not setting out to know at least the fundamentals of the subject. Fundraising leaders should insist upon their staff being steeped in it. We can’t be surprised that the likes of Guinness and the major supermarket chains are so much better at it than are charities – despite the fact that we have the best stories in the world to tell and the best of reasons for telling them well, with power and passion that will move people to action.

For those keen to gain a competitive edge Francesco Ambrogetti’s book Emotionraising can be found here. And CDE’s project 6 in its entirety can be found here. If you accept that you don’t know all you should about the use and misuse of emotion, these might be good places to start.

Part 2 of this feature, Three steps to transform how fundraisers communicate emotionally, sets out how and why we need to tell our stories differently, and is linked here.

© Ken Burnett 2021.

This article appeared on Ken Burnett’s website in 2019.

Related articles • The Emotional Brain. • Straight to the heart of how fundraising works. • CDE project 6, the use and misuse of emotion full contents and purpose.

This article first appeared on the Institute of Fundraising's website, here and here.