The gold standard in fundraising, part 1: laying the foundations.

Giles Pegram of the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NSPCC) and Redmond Mullin of Redmond Mullin Limited describe how a seminal five-year fundraising campaign irrevocably transformed the fortunes of one of Britain’s top charities.

- Written by

- Ken Burnett

- Added

- April 08, 2010

View original image

View original image

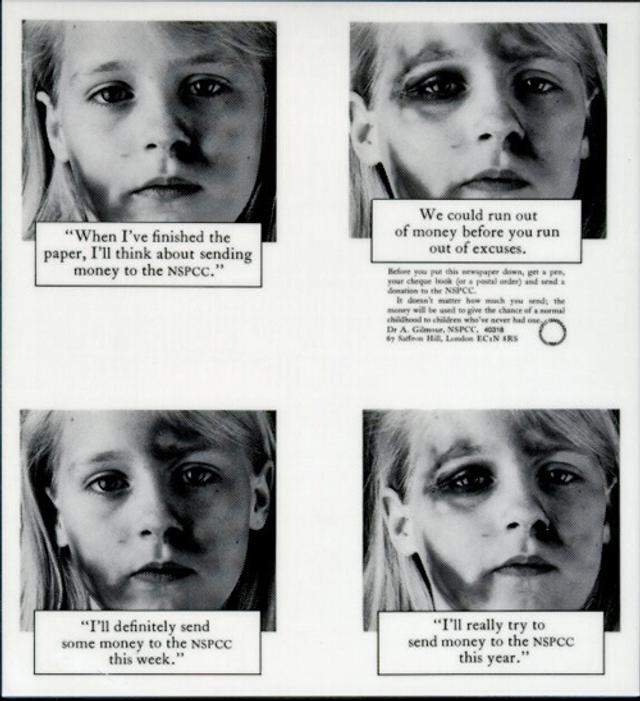

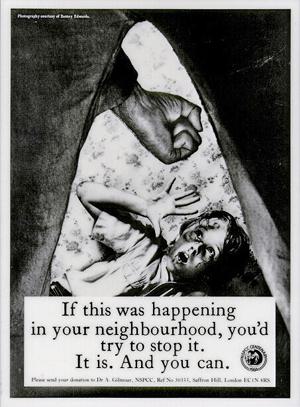

To understand the impact and importance of the NSPCC’s famous Centenary Appeal you have to go back in time more than 30 years, to 1980, when you would find a very different NSPCC. The NSPCC is a household name synonymous with the highest standards of childcare, a ceaseless and highly effective campaigner against all forms of child abuse. In 2009 the NSPCC’s annual income topped £156 million. It’s reputation for ambitious, effective and innovative fundraising is now second to none, worldwide. Yet back in 1980, though the NSPCC was an honoured, respected and well-known name with an enviable history, its finances were in a parlous state. Annual income was just £2 million and there was less than two weeks operating costs in reserve. In the nation’s list of top charities NSPCC ranked well below its traditional rival, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (RSPCA), a clear signal then of the British public’s priorities in terms of charitable giving: animals came well ahead of children.

NSPCC wasn’t telling its story properly . It was part of the establishment and, as such, the presumption was that surely it didn’t really need money.

The time was right for an ambitious new approach, even if that meant taking some risks. A young professional fundraiser called Giles Pegram had been recruited in 1979 as director of appeals and publicity. Structurally Giles’ appointment was at a more senior level than other reports to Dr Alan Gilmour, the Society’s director at the time. Giles was not just head of the major public functions, he also rejoiced in the additional title of assistant director. This was deliberate: a small but significant sign of the importance that the Society was now prepared to give to fundraising.

Inspired risk-taking

Still many of the Society’s trustees and senior supporters doubted the potential for fundraising to turn things around. So Giles Pegram saw that he needed help. He had also realised that an important anniversary for the organisation was looming – founded in 1884, the NSPCC was just four years away from its hundredth birthday. Although public fundraising campaigns for the universities of Cambridge and Oxford were ongoing at the time, no national charity had ever launched a major capital campaign. The vision he conceived was therefore not just bold and daring, it was unique.

Four years before the anniversary Giles appointed renowned consultant Redmond Mullin to guide the Society through the planning and implementation of a strategy that would raise enough money to transform its fortunes and elevate the charity into a different league. It was to prove an inspired appointment. The two formed a working partnership that still endures and has successfully steered the NSPCC through not just one but two of the highest profile public campaigns in British fundraising history (The story of the NSPCC Full Stop campaign will soon be featured on SOFII too.)

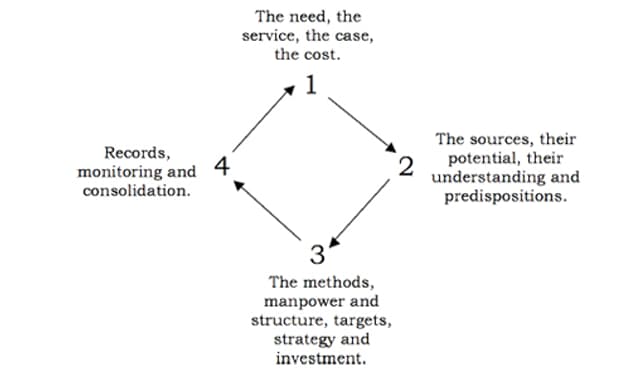

The Fundraising Cycle: the shortest book on fundraising, ever

The Fundraising Cycle: the shortest book on fundraising, ever

The long lead-time created for the Centenary Appeal was also inspired. Far too often the planners of large-scale capital campaigns fail to invest adequately up front and to allow sufficient time to plan and put in place the necessary infrastructure and ingredients for success. These shortcomings almost invariably lead to underachievement, and often to failure.

Both Redmond and Giles were well aware from the start that a hundred years of existence was no reason why anyone should do anything. But it was a focus. To work, their campaign had to be made significant. Both knew this would require a lot of planning, dedication, insight, understanding and considerable risk. So a bit of luck would be useful too.

Fortuitously the thinking in professional child-care was moving from the lone social worker, or inspector – the cruelty man – to the idea of small specialist teams, the child protection team. The Centenary Appeal would therefore raise money to put a network of 60 new teams in place across the country.

When a failure proved infinitely preferable to a success

Giles Pegram recalls that the NSPCC had almost no resources for fundraising back then. The whole fundraising infrastructure consisted of a network of branches in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, a special events team around the country and very little else. A complete gearing up was needed to embrace communications, press and publicity, direct marketing, corporate fundraising and just about everything else besides.

The need for an all-encompassing and effective strategy was paramount. As nothing quite like this had been done by a charity before, the duo had to make a lot of it up as they went along. They would meet for breakfast at the St George’s Hotel, not far from the NSPCC’s offices near the BBC, in London’s West End. Redmond recalls that the whole strategy for the campaign was scribbled out one morning on a tablecloth complete with coffee stains and bits of marmalade. This scribbled strategy set out the basic structure that held throughout the four years of preparation, the year itself and the aftermath. Among the crumbs and stains was a structure including a main committee, sub-committees for the regions, industry, media, press and philanthropy.

Their ambition was enormous. A favourite anecdote from the early days of the appeal concerned the setting of the target and the trustees’ approval of it. Giles recalls.

‘We wanted to aim high, so we planned that the overall target should be £12 million. That may not sound so high nowadays, but then it was a huge, almost inconceivable sum, enough to free us to do what we needed to do. And a stretch – six times our current annual income.’

The trustees’ initial reaction was that such a sum was quite out of the question. At their meeting a redoubtable and very famous lady of the aristocracy rounded on Giles, saying that if they aimed for £12 million they would certainly fail. ‘You must set a target for £5 million,’ exclaimed her ladyship, ‘then you will certainly succeed.’

Calmly Giles Pegram agreed with his formidable trustee that they would surely achieve a £5 million target, whereas if they aimed for £12 million they might indeed fail and only raise £8 million.

‘But which is better,’ he proclaimed, ‘a £5 million success? Or an £8 million failure?’

This logic convinced the wavering trustees and the target was set at £12 million. In the event, they raised £15 million.

The Great and the Good

One thing very much in the NSPCC’s favour was that the organisation is undeniably well connected. Princess Margaret, sister of the Queen, was a very active patron. Her presence alone ensured strong engagement from many sectors of the aristocracy, political and show business figures and captains of industry. The prime minister of the day, Mrs Margaret Thatcher, was also well known to be a staunch NSPCC supporter. Pegram and Mullin decided to exploit these connections vigorously.

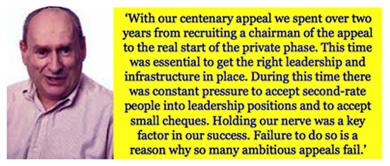

‘The timing of all this was crucial,’ recalls Redmond Mullin. ‘We had to get the right leadership in place and make sure that not a penny was asked for, by anyone, until it was.’

Again, this is an area where faint-hearted fundraisers frequently lose their nerve, with catastrophic consequences.

A lot of work went into identifying, selecting and then recruiting the right individuals. An early key player was noted industrialist Sir Maurice Laing, chairman of the John Laing construction group, who right at the start told Redmond that he wasn’t going to get involved. But he did agree to give his advice, which the fundraising pair called upon heavily whenever they could. Sir Maurice eventually realised that his role within the campaign had been quietly assumed. On one occasion he was overheard saying, ‘I’m now so far down the slippery slope, there’s no way off.’ He became a highly effective joint chair of the industry committee with fellow captain of industry Gerald Ronson. They were entirely different characters, but they worked very well together.

Leadership is crucial in any capital campaign (see the Wishing Well Appeal on SOFII). Pegram and Mullin decided that rather than one large, all-powerful committee, their appeal really needed a very active chairman. The ideal candidate was identified as the young, charismatic and very well-placed Duke of Westminster. The only problem was he had no previous relationship with the NSPCC whatsoever.

Yet, he agreed. When later asked why he had consented to such a demanding, time-consuming role (as he became more committed it grew to become an almost full-time job for the young duke) Gerald Westminster gave a quite simple explanation. He said, ‘I was approached by a trio of formidable women to whom I just couldn’t possibly say no.’ These were Princess Margaret, Mrs Thatcher and the Chair of Council at the NSPCC, Lady Holland-Martin.

One has some sympathy for him.

The Duke of Westminster was the first to admit that he learned a lot from his time as chair of the NSPCC Centenary Appeal; and he also enjoyed most of it hugely. A favourite anecdote of his involved the time, at a quite advanced stage of the campaign, when he decided to call personally on many of the heads of Britain’s leading companies, to solicit their donation. The Duke is landlord of much of the exclusive London region of Mayfair, where many corporate head offices are based. Word had got around that Westminster was calling on his tenants and that they were each being asked to cough up serious money (such a tactic would, of course, have been rather unusual at the time). But no one would think of refusing a visit from the Duke of Westminster. When he came to call upon the head of one very large company he was ushered in to a plush office where his host met him with the exclamation, ‘How much do you want?’

The man had his chequebook already open and was prepared to sign a cheque, there and then. Gerald Westminster was quite taken aback. Thinking on his feet he blurted out the first large sum that come into his mind. ‘One hundred thousand pounds.’

His host looked at him and smiled. ‘Oh that’s good,’ he said. ‘I thought you were going to ask for £500,000.’ And he signed the cheque and handed it over immediately.

This, the Duke of Westminster later avowed, was when he learned the crucial importance of asking each donor for the right amount.

It’s a lesson every fundraiser should heed well.

NSPCC’s major transformational appeals

NSPCC: the Centenary Appeal, setting the gold standard in major campaign fundraising, from 1984. This is the main exhibit for the NSPCC Centenary Appeal.

The gold standard in fundraising, part 1: laying the foundations.

The gold standard in fundraising, part 2: exceeding expectations.

NSPCC: the Full Stop Appeal