The gold standard in fundraising, part 2: exceeding expectations.

Giles Pegram of the NSPCC and Redmond Mullin of Redmond Mullin Limited conclude their two-part special feature on the historic NSPCC Centenary Appeal, from 1984.

- Written by

- Ken Burnett

- Added

- April 08, 2010

The first of these two articles explained how, in the early 1980s, Giles Pegram, newly appointed fundraising director for the NSPCC (the National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children), got together with eminent fundraising consultant Redmond Mullin to plan and create the first major capital appeal in modern times from a top UK public charity. They conceived their ambitious strategy not quite on the back of an envelope – it was instead scribbled on a paper tablecloth over a breakfast meeting at the St George’s Hotel in London, simply because no envelope would have been quite big enough for the task.

Giles and Redmond had made a brilliant choice in their recruitment of a campaign chairman, the young and energetic Duke of Westminster. One of their early tasks involved the organisation of a high-powered meeting of major players at which their elaborate and complex new strategy would be unveiled. Among the Duke’s early tasks was the chairing of that meeting and the securing of commitments to actions that would arise from it. As luck would have it only three of the carefully targeted individuals turned up, nevertheless Giles and Redmond presented their strategy. The meeting was suitably convinced and their collective response, in summary, was, ‘That all sounds incredibly impressive. How many people have you got involved, so far?’ To which the Duke hesitatingly responded, ‘Well, apart from me, there’s, well... you three.’

View original image

View original image

Just three they may have been. But each was an influential captain of industry and each undertook to throw his energies into the ambitious cause that had just been set out before them.

In describing the anticipated demands of his role as appeal chairman Giles and Redmond had innocently suggested that the Duke might expect to chair four meetings in the course of the year, with perhaps a few other duties on top. That it had sounded so easy was undoubtedly partly responsible for his agreeing to take on the role, but he was soon sucked in and found himself doing what amounted to a fairly full-time job. The NSPCC recruited extra people for several areas in anticipation of the coming campaign, not least of which was in the team of back-up staff assigned to working with the committees and supporting the Duke.

‘A lot of people think you magic appeal committees out of thin air,’ observes Redmond Mullin. Clearly that’s a mistake. ‘The process is long, tortuous and difficult – if you are going to get the right people. If you are prepared to accept the wrong people then it is easier, of course. But the problem with that,’ Redmond continues, ‘is that once you’ve got them the wrong people can be very difficult to get rid of.’

The founder of the retail chain Habitat, Sir Terence Conran, a member of the main committee and leader of the NSPCC’s retail committee, compared his election to this august group as, ‘Like being invited to join the Government.’ It was little exaggeration. The key considerations when assembling the right committee are

- The ability to say no firmly. You must not have people ‘wished upon you’.

- A clear structure, with a target and end in view.

- Sufficient investment in the right internal resources, to support the committee.

- An active and positive appeal chair. This role is crucial.

- The trustees have to invest for two or three years before they will see any return.

The constant courage and commitment of trustees is a recurring theme of any conversation with Messrs Pegram and Mullin about the Centenary Appeal. Both feel the importance of this cannot be underplayed. NSPCC’s trustees were so committed to the grand design the duo had hatched that they invested the last of the Society’s ‘rainy day money’ in it.

‘What else are reserves for?’ you might ask. Obvious, perhaps, but few trustee boards are sufficiently gifted to see it that way. Giles Pegram started to put in place elaborate though carefully researched plans for direct marketing, trust and foundation fundraising, corporate campaigns and a range of other initiatives. All of these made perfect fundraising sense, but all were areas that hitherto the NSPCC had not even dabbled with. And each required substantial investment before any return could be reliably predicted.

The sequence of events

The first meeting of the Centenary committee was held in the spring of 1983, nine months before the start of the centenary year.

The second and most important meeting took place in October of that year. By then, most of the appeal structure was firmly in place and working well. The committee had set targets for all components, and each knew their own, but no one knew the targets set for other committees or activities, nor did anyone other than Giles and Redmond know how these targets all came together to achieve the whole.

It was time to share this information more widely.

The Duke of Westminster started the October meeting by solemnly going round the assembly asking everyone to volunteer the targets they were committing to while Sir Mark Weinberg, head of Allied Dunbar Insurance and honorary treasurer of the appeal, dutifully totalled each pledge on a large calculator. He then gravely announced the total of all these pledges. It was £13 million. For the first time, all the key participants could see that the overall target was indeed achievable – but only if each component delivered on its pledge and achieved or exceeded their own individual target.

Giles and Redmond had known this in advance, of course. But now they had commitments from all key players, each of whom had publicly acknowledged his or her ownership of one part of the final appeal.

‘It was really a landmark meeting,’ recalls Giles. ‘We knew the totals in advance of course, but they didn’t. The cumulative effect of all the targets coming out like this was electric. We had ownership.’

Of course some committees worked less well than others and a few worked less well than they should. But faltering committees and committee members were supported and shored up by the centre and by their fellows. A healthy competitive atmosphere had been created that sustained everyone in what all knew would be no easy task.

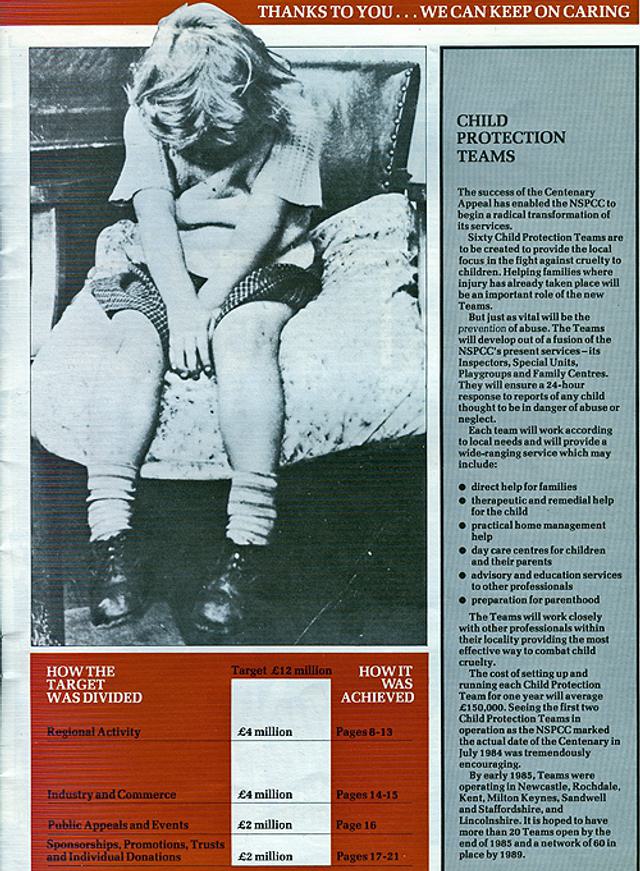

With the private phase already well underway and accumulating pledges all the time, the NSPCC Centenary Appeal was publicly launched towards the end of 1983. Activities marking the year itself started on 1 January when Lisa Bocarra, a London schoolgirl representing the ‘Give an Hour for a Child’ part of the campaign, presented Princess Margaret with a jar of pennies. The top London store Selfridges created a ‘Mountain of Pennies’ in its basement, which attracted huge publicity. Collecting boxes, the contents of which went to build the mountain, were placed at every railway station in the country. Major retailers across the country mounted joint promotions that raised huge sums for the appeal. NSPCC regional supporters groups began a year-long calendar of events large and small of every kind and description, all raising money and spreading the word. Not long into 1984 it would have been hard to find anyone anywhere in the British Isles who was unaware that this was the NSPCC’s very special centenary year. By the end of 12 months of extraordinary effort and activity up and down the land the NSPCC, from all sources, had indeed achieved and even exceeded its target of £12 million.

But still the money kept coming in. And even after the end of centenary year there was a lot to think about, to plan for and to do.

Who is in the driving seat?

Led by Redmond and Giles the pace and momentum of the campaign up until that crucial meeting in October 1983 had been driven and maintained by the NSPCC’s professional staff team. After the October meeting, crucially, the pace transferred to the volunteers. Redmond believes that a critical mass was reached at precisely the right time. ‘These things work best when they happen naturally,’ he says. ‘But happen they must.’

The prime minister of the day, Mrs Margaret Thatcher, played a surprisingly important part in the overall success of the appeal, showing on more than one occasion that she would have made a great fundraiser. She hosted several receptions and a dinner at No 10 Downing Street. Her style was interesting. One leading volunteer described her as, ‘taking him by the ear’ to meet the Duke of Westminster, who then spelled out what would be expected of the hapless volunteer during the campaign. Gentle arm-twisting might well have been noted at the time, but equally there was a cachet attached to being close to the inner workings of the NSPCC’s appeal, so genuine volunteers were not in short supply.

When the target was reached, comfortably before the year’s end, it was clearly a time for celebration. But Giles and Redmond had already anticipated that there might be something of a come down afterwards, once the first joy of achievement had died away.

To a large extent this natural reaction had been countered by Redmond Mullin’s insistence that the NSPCC should start the planning process for consolidation half way through the actual centenary year. This meant that slap in the middle of the busiest fundraising campaign of their lives he and Giles were asking everyone to spend time planning for what would happen after the event. It seemed a crazy step too far at the time, but turned out to be hugely prudent. Given how much there is to do in the months after a major appeal it’s vital that the machinery doesn’t unravel too early.

One consideration is what to do with all the volunteer talent that the appeal had brought in and developed. ‘We found this divided roughly into thirds,’ explained Giles. ‘One third of our volunteers we didn’t want to keep, the next third we might have wanted but they had clearly had enough so didn’t wish to go on. The final third we really wanted to keep and to find productive things for them to do.’

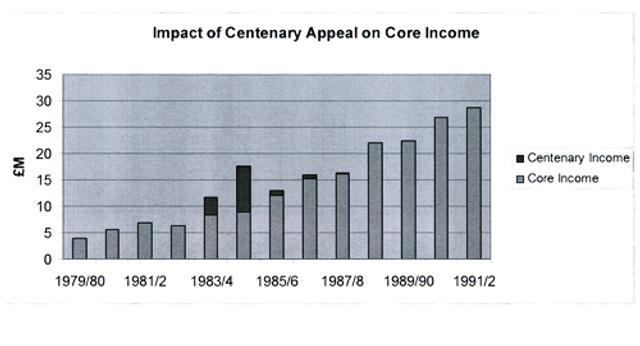

From the start a worry for many associated with this campaign had been that once it was over the NSPCC’s core income would fall back to something like it had been before the Centenary Appeal started. Redmond Mullin expected a quite different outcome to prevail and not for the first time he was proved right. There was indeed a small dip in core income immediately following the centenary year but, as the chart above shows, the effect of this major activity was entirely benign. Instead of falling back to where it had been the Society’s income was ratcheted up to new levels from which it has never fallen. This same effect was experienced years later with the Full Stop Appeal.

At the end of the affair

The Centenary committee stood down at the end of 1984 and a new body was formed – the Corporate Development Board. Sir Maurice Laing and Gerald Ronson, joint chairs of the Industry Committee, continued their successful double act heading this new board. The Duke of Westminster had worked himself into the ground with the Centenary Appeal so, quite appropriately, he took the opportunity now to stand down.

The Corporate Development Board continued because the potential for effective co-operation with industry had been strongly demonstrated during centenary year. It seems hard to credit it now but corporate social responsibility was barely understood in the UK before 1984 – you just didn’t see companies forming major relationships with charities. The NSPCC Centenary Appeal changed all that forever. Many national and international companies had seen clear benefits from associating with the NSPCC. Employee morale had shot up at the Laing Group directly because of the NSPCC’s involvement as their charity of the year. And sales shot up too. Other companies told similar stories. A new age of corporate fundraising was born.

But Giles Pegram denies that the Centenary Appeal was intrinsically innovative. ‘Many innovations arose out of it,’ he says modestly, ‘but really we were more aspirational than innovative. We really went back to basics, to capital appeal fundraising as it should be done, as Redmond had set out in his books.’

There were some disappointments, of course. At the end of the campaign a number of good employees elected to move on, perhaps believing that the excitement of recent months would be difficult to maintain. There was a period of post major appeal depression, but the NSPCC came out of it quite quickly. Looking back, the real challenge came after the target had been reached, when everyone still had to keep going. But there were huge satisfactions from the big appeal. It had galvanised and revitalised the organisation, giving it a new impetus and momentum. And the benefits for children were considerable. Thanks to the Centenary Appeal the NSPCC was able to totally reorganise, modernise and re-equip its new childcare teams. There was no looking back.

Giles Pegram considers that the most important lesson of all comes from this realisation. ‘It was the fundraisers, pushing for a reason to give that encouraged and cajoled the rest of the organisation into the massive change it needed. In 1983 the NSPCC knew it wanted to move from lone inspectors to child protection teams, but it agonised over details - exactly how many protection teams were needed, where they’d be located and when they would be open. Finally I asked, “Can we say that we aim to set up at least 60 child protection teams over the next five years?” A two-minute discussion produced the answer – yes – and so we had a fundraising proposition and an action plan. But at all times it has to be what will transform childcare, not merely what will work for fundraising. The achievement isn’t just money or a sounder organisation. It’s a huge difference for abused children.’

Makes it all seem simple, doesn’t it?

Success in a major capital appeal absolutely requires a big idea that will catch people’s imagination. It also needs ambition of a different order of magnitude. Sadly people seem more risk averse nowadays, so transformational change on this scale is rare. Yet every charity has within it an implicit vision of transformation. Only a few will rise to the opportunity, and only some of these will succeed. As always, the only answer to the inevitable question will it work for us? is, yes, but only if you do it right.

Perhaps the public might assume that the opportunity to make a real difference for our cause is simply a given, for fundraisers. Giles Pegram is often reminded that he was quoted a while back as saying that he was still doing the same fundraising job 30 years later because, ‘there really isn’t anything more important to do.’ He now qualifies that.

‘I wouldn’t be happy to be appeals director here after all this time if we hadn’t, at least twice, aspired to completely change the scale of our ambition, to turn everything on its head.’

For both the NSPCC Centenary Appeal and its direct descendent, the Full Stop Appeal, the scale of ambition came from a sense that, for these people, ‘good enough’ is simply not good enough. There was no scientific rigour. It was a transformation literally mapped out on a stained paper tablecloth. Not just once, but twice, it transformed the prospects, style and approach of an organisation.

I’m not sure what the right word for this is. Chutzpah, perhaps. Though seldom sure how to spell it or pronounce it, most people know what it means well enough.

It’s a chance to make a difference, to really change the world.

It’s a good enough reason to be a professional fundraiser.

NSPCC’s major transformational appeals

NSPCC: the Centenary Appeal, setting the gold standard in major campaign fundraising, from 1984. This is the main exhibit for the NSPCC Centenary Appeal.

The gold standard in fundraising, part 1: laying the foundations. The gold standard in fundraising, part 2: exceeding expectations.

NSPCC: the Full Stop Appeal