CDE project 6 section 5.5: Seven more big things to think about

The use of emotion in fundraising communications is critical and expansive. Here from CDE project 6: the use and misuse of emotion, are seven further big things to consider when dealing with emotions

- Written by

- Ken Burnett

- Added

- October 18, 2018

CDE project 6: the use and misuse of emotion.

Section 5.5a:

Seven more big things to think about

Because charities — good causes — have the best stories in the world to tell and the best of reasons for telling them, the Commission on the Donor Experience believes that charity fundraisers should tell emotional stories at least as well as anyone. If not better. Fundraisers, undoubtedly, have to tell their stories not just well but also with power, passion and purpose to move people to action to change the world for the better.

‘The great enemy of clear language is insincerity’

George Orwell, Politics and the English language, 1946

And because CDE believes that donors, their interests and comfort should be at the heart of fundraising strategies, always taking precedence over financial targets or growth objectives, emotional stories will have to become the currency of fundraising organisations everywhere. Of course emotions always have to be used honestly and honourably, with great care for the comfort, acceptability and appropriateness of all fundraising messages.

In this short piece I’ve included brief information on some aspects of emotional fundraising that will repay further study. I’m not attempting to explore these issues in detail but merely to introduce the subjects and to show that in this fascinating field, there really is so much more to learn.

- Finding your WHY and an introduction to chunking.

- The power of reciprocity.

- Empathy and rapport.

- Simulacrum and other such stuff.

- Framing.

- Putting passion back in fashion.

- The five Fs in action and the truth, told well.

Why finding your ‘why?’ is so important

‘It always comes back to “the why?” Let’s start with why ‘THE WHY’ is so important. Cost effective marketing has moved from broadcasting a message to being a conversation. We are all now a channel. Much fundraising still focuses on the transaction – how to get money out of me. It's probably why the message is all about what we do, not why we do it. It's why fundraising can be seen to be too pushy to achieve its aim of getting me to give. And if I have a bad experience, too bad, just line up the next person to ask.’

- Richard Turner, on Alan Clayton’s website, July 2016

The WHY is about your cause and why anyone should care. Simon Sinek’s TED talk Start with WHY is, as its name suggests, a good place to start. It’s ‘wow!’ rather than ‘so what?’ It shows how people don’t buy what you do, they buy why you do it.

Chunking up and down to find your WHY

‘Chunking up is moving from the detail to the bigger picture, the vision, why we are here. Chunking down is the reverse, moving from the big picture into the detail of how it might be delivered. It’s a simple technique often associated with neuro-linguistic programming (NLP).

Chunking is a powerful and hugely useful tool, particularly for individuals and organisations who want to tell transformational stories. It’s so strong and helpful that my partner Alan Clayton refers to it as the magic superhero power. It really does blast away organisational clutter and extraneous detail to get to the emotional heart of what a cause or organisation is all about.

Typically people in big organisations share the same big picture of what they’re there for but can rarely agree on the nitty-gritty of how to get to it. To move from the detail up to the big picture, just keep asking the question why? Or, ‘what is the purpose of..., or the reason for...?’ To chunk down, ask, how? Or, ‘give me an example, explain...’ Put simply, keep on asking why until you get to what. On the way, you’ll probably find the moment when something changed.

Asking why takes you in a completely different direction from asking how. A good example of chunking up is how, in 2005, London won the bid to host the 2012 Olympics, when Paris was already hot favourite and had most of the votes already in the bag.

Or so most people imagined, until London delivered its two-hour presentation.

In their respective presentations each competing city had the chance to include a short film. Traditionally these videos feature an elegant, attractive, smartly-dressed presenter with sparkly teeth and neat hair zooming round the city by helicopter showcasing its amenities to the earnest description of building plans, legacy, traffic flow and the athletes’ accommodation.

London did none of that. They chose not to feature their city at all, mentioning it just once at the end. Instead they focused on the dream, through the stories of four young athletes from different corners of the world who were inspired to compete alongside the cream of the world’s best, to give their all for the Olympic ideal. The result is a beautiful, highly emotional example of transformational storytelling.

In planning this presentation the London committee, just like all its competitors, must have had members reminding them that they were expected to feature their parks and skyline, to explain how they would keep the city moving, show their superb facilities and all that stuff. But someone then cut through that clutter to insist, ‘it’s all about the children’. As committee members pressed their case, this lone advocate somehow stuck to his or her guns saying, ‘No, no. It’s about the children!’

That’s why London won the day. They had a dream and stuck to it; the big picture, what was really important. And they told the story powerfully, visually and with emotion to move those wavering voters to change their minds. See their short video here.

For years a leading environmental charity believed that its role was to protect birds and that its supporters were largely the kind of folk who wear bobble hats and sit for hours in a field, waiting for something to fly within range of their binoculars. Then this organisation chunked up and realised that to save the birds you have to save the sky, the biggest thing there is. If you save the sky you also must save the land and the sea. Before long it seemed obvious that, really, saving the birds for future generations to marvel at and enjoy is really all about children. It’s about the future, the imperative that generations as yet unborn might grow up in a world full of sparrows, eagles and the dawn chorus. Soon the organisation realised that they weren’t just a charity for bird-watchers, they were a charity for children. Explain what your prospect’s children and their children’s children will get out of their support for your cause and people will get involved, big time. That’s the power of chunking up. SOFII has an exhibit that shares the detail, see here.

When Norway’s Strømme Foundation launched their revolutionary Jobbskaper scheme (https://strommestiftelsen.no/jobbskaper) they too were chunking up. They realised their work as micro-credit for small businesses was really about job creation. So they repackaged it, then focused on a target for one town, imaginatively involving everyone living there in a drive to create thousands of jobs. Simply by chunking up they moved from the mundane mechanics of a worthy scheme to re-presenting those same outcomes as an easily identifiable, shareable dream, which had a much stronger chance of appealing to sponsors and donors who want to change the world – the job creators.

Simply put, chunking helps an organisation to find its emotional heart.’

The above section on chunking is adapted from Storytelling can change the world, by Ken Burnett, published in 2014 by the White Lion Press.

So fundraisers, start with the WHY, not with the WHAT. And use chunking to help you find it. If you haven’t yet captured and defined your WHY, get on with it. There’s not much that’s more important.

Putting passion back in fashion

Passion is important. Yet like emotion, it’s something some fundraisers get all queasy about, so shy away from. Maybe men suffer most from this, as so many men feel they’re not meant to be passionate or emotional.

It’s a big mistake to imagine this. For a fundraiser, it’s catastrophic.

For 2016’s IoF National Fundraising Convention I was given the chance to be part of the opening plenary session, talking about relationships and passion. The whole session was dedicated to capturing lessons from the extraordinary fundraising experience of Tony Elischer, who died tragically young at the start of 2016.

I’ve edited just a few minutes from that session for this project, because what I was able to say then about passion also seems to fit here. Have a look at 5.5 Ken B on passion:

These slightly less than five minutes of video come from the Institute of Fundraising’s filming of the entire plenary session, which can be found here.

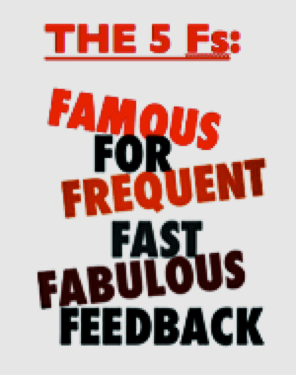

Communicating the passion via the 5 Fs

There’s no point in being passionate or inspirational if you can’t get the inspiration out there. That’s why our organisations and the individuals within them all have to determinedly pursue the policy of the 5 Fs – to be Famous for Fast, Frequent, Fabulous Feedback. At the time of writing our sector is anything but good at feeding back with wonderful stories about the good things their donors have enabled them to achieve. It’s curious, because charities do make a great deal of difference. Yet they communicate the fact very badly, or inconsistently at best.

The 5 Fs. That’s what our sector so obviously should be, but simply isn’t. Famous for frequent fast fabulous feedback. Donors invariably want to know, quickly, what a difference their gift made. Saying thank you nicely is just a part of this, as is ‘Well done, congratulations, you’ve just done something wonderful.’

Planting a commitment to the five Fs in your organisation could be an easy quick win. Implementing it could easily and vastly improve your donors’ experiences.

Information is putting out, communication is getting through. Communication is the fundraiser’s most crucial core skill yet few are specially trained in it or much good at it. How fundraisers should review the use or misuse of emotion in their fundraising communications, to ensure that donors are inspired rather than distressed by emotional images and messages. Cornerstone of the relationship fundraiser’s use or abuse of emotion has to be the concept of the truth, told well.

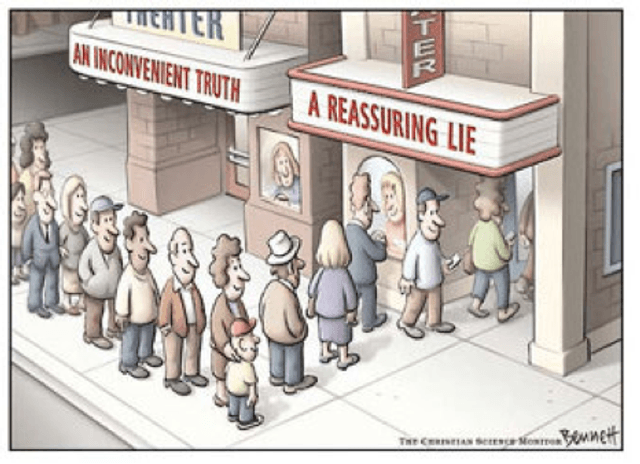

The truth, told well

I came upon this slogan some years ago. It’s the catchphrase of the advertising agency group, McCann-Erickson, and how I wish it were the motto of all transformational storytellers everywhere. The truth, told well. That’s all we should aspire to, to win the hearts and minds of our audiences. ‘True’ is a good adjective to attribute to people. People aspire to be true to a cause, to a mission, to a vision, to a dream. It’s a good sentiment to work into your writing. Psychology professor Jen Shang has discovered in her research that people describe a ‘moral’ person or a ‘good’ person using primarily nine adjectives: caring, compassionate, friendly, fair, generous, hard-working, helpful, honest, kind. A good addition to that list might be ‘true’.

The magic of reciprocity

This is about give and get, not just get.

Rather obviously, donors are not cash machines and any relationship built upon incessant asking and one-way traffic is never going to last. Fundraising isn’t just about ‘they give, we get’. Donors have to get a lot from the relationship too or they’ll quickly stop giving.

Just about everybody in the marketing or communications business knows that back in the 1980s Professor Robert Cialdini and others showed convincingly that reciprocity works, that if you do something for someone first, they are more likely to reciprocate. And, the favour that you offer doesn’t have to be equivalent – a small favour can lead to a much bigger return favour. It’s a reliable human attribute invariably driven by emotion.

The story of an early practical example of reciprocity in action is told here:

Simulacrum

This arcane-sounding term simply means intentionally distorting an image to make it appear correct to viewers, or to influence their perception of it. A caricature; a distorted representation of reality that’s common in art, fairy tales and how we explain things to children. Sugar-coating experiences. Though frequently benign, the practice is often frowned upon. In my early days in the sector, when I made a living of sorts producing annual reports, annual reviews and so forth for charities I was sometimes asked to angle the pie charts that invariably accompany financial reporting in such a way that expenditure on overheads were to the back, so in a three dimensional chart they invariably looked smaller.

I refused, of course.

Simulacrum has long been of interest to philosophers. In his Sophist, Plato speaks of two kinds of image making that was popular among sculptors at the time. The first is a faithful reproduction, attempted to copy precisely the original. The second is intentionally distorted in order to make the copy appear correct to viewers. He gives the example of Greek statuary, which was crafted larger on the top than on the bottom so that viewers on the ground would see it correctly. If they could view it in scale, they would realise it was malformed. Apparently, so Wikipedia tells me, this example from the visual arts serves as a metaphor for the philosophical arts and the tendency of some philosophers to distort truth so that it appears accurate unless viewed from the proper angle.

An interesting example of simulacrum is caricature. When an artist produces a line drawing that closely approximates the facial features of a real person, the subject of the sketch cannot be easily identified by a random observer; it can be taken for a likeness of any individual. However, when a caricaturist exaggerates prominent facial features a viewer will pick up on these features and be able to identify the subject, even though the caricature bears far less actual resemblance to the original subject. A good example is the caricatures Gerald Scarfe prepared for the opening credits of the Yes Prime Minister hit TV series of the 1990s. The noses of the three lead characters in his drawings are so exaggerated as to be totally unlike those of the real people. Yet they are all instantly recognisable.

Simulacrum should be important to fundraisers because we have to take care when communicating, to avoid exaggeration, simplification and sugar-coating. But, I accept this needs some development.

Empathy and rapport, the best way to change the world

In an article on LinkedIn called How Empathy May Be Key to Our Survival, Claire Axelrad CFRE suggests that empathy may be the foremost survival skill of the current age and the very best way to change the world. She even suggests that it ties back to Darwin’s theory of survival, which instead of being labelled survival of the fittest, Claire thinks should be labelled ‘survival of the most empathetic’. ‘Darwin,’ Claire says, ‘argues that we are a profoundly social and caring species, with sympathy being a stronger instinct than self-interest.’

Empathy is fellow felling, our ability to put ourselves in donor’s shoes, to see things through our donor’s eyes. A bit personal and invasive, perhaps. But something that donors might expect to experience more from people that contact them from the charities that they support than from, say, salespeople from their insurance company or reps from their double glazer.

Rapport is a close and harmonious relationship in which the people or groups concerned understand each other’s feelings or ideas and communicate well. Methods of building rapport include using similar body language – posture, gestures, expressions – maintaining eye contact and matching breathing rhythm. It’s about being on the same side, sharing the same feelings rather than facing each other in confrontation, across a table. Arms draped round each others’ shoulders rather than one twisting the other’s up his or her back.

Empathy-based design is a concept that Adam Willis has written about (see CDE 6 section 5.5b). Adam is a recently graduated young graphic designer and communicator of considerable talent. His final year dissertation is worth attention. As with reciprocity, Francesco Ambrogetti has interesting things to say about empathy and rapport in CDE 6 section 3.1.

Framing

Stellar international fundraising consultant Matthew Sherrington explains this phenomenon.

‘One of the things fundraisers have long struggled with is their charity’s discomfort with emotion; the suggestion that emotion means dumbing down, isn’t serious or credible. It happens everywhere. Emotion, and the simplicity of a message, are sometimes disdained by other colleagues as patronising to the audience. It is anything but – it shows respect, meeting, connecting and engaging people where they are. It’s not just ‘what works’ in fundraising, it’s fundamentally how we all respond to events and make decisions. It’s how we’re hard-wired.’

‘Why is it,’ Matthew asks, ‘that the poorest states in the USA are also the most Republican?’ People consistently elect politicians hell-bent of acting against their economic interests with policies that make them poorer.

Matthew reckons we only need to look at the now not-so-recent UK referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Economic Community, the so-called ‘Brexit’ debate. ‘Leavers’ had no plan so they had no facts, just the emotional power of their argument for identity and control. ‘Remainers’ had the economic facts (some less credible than others, let’s be frank), but couldn’t muster any emotional enthusiasm for the EU, cloaked as it was with caveats of necessary reform.

‘So people voted emotionally, not practically, right?

Matthew continues. ‘In an earlier US election people could imagine having a barbecue and beer with cowboy George Bush, but not doing small talk with windsurfing John Kerry. What they said didn’t matter. How people felt about them did, the feeling that they had more in common with one than the other. So Democrats started to learn about ‘framing’, which the Republicans had been doing for years. (You could take this argument a lot further, re the subsequent election in the US of one Donald Trump.)

‘It’s all about tapping into people’s emotional frames of reference. What they care about. What they identify with. Not just the issues but the values through which they relate to those issues. The Scottish referendum was also a case in point. The No vote tapped into fear, which proved stronger than hope.

‘There are some charity leaders who are brilliant at conveying the essence of their cause and mission with simplicity and raw, emotional power, who can tell a good story, wear their heart on their sleeve and aren’t embarrassed to do so. They set a great example. To get their organisation’s culture to follow and embrace emotion is the new communications frontier.’

According to seasoned fundraiser and CDE commissioner Rachel Hunnybun, getting the basics wrong in fundraising is so damaging it can outweigh getting the wow moments right.

‘Our brains,’ says Rachel, ‘place expectation on everything that we do, sometimes from past experience, but where we don’t have a past experience to refer to, we make a reasonable assumption. So in the case of some shoes I recently purchased on line, whilst I hadn’t purchased from the company before, from past online purchasing experience I had a reasonable expectation that both pairs of shoes I ordered would be delivered pretty much on time.

‘When those expectations are exceeded, the brain releases dopamine (a happy chemical), but when what we expect isn’t delivered, we feel disappointment. No dopamine and instead the brain disrupts the flow of serotonin (another happy chemical). Research has shown that the emotions associated with bad service, e.g. disappointment, anger and irritation, can last significantly longer than emotions we would associate with great wow moments – feelings of surprise, being touched and gratitude. So delivering what our supporters expect is absolutely crucial for a good experience.’

© Ken Burnett 2018

For the full contents list of CDE’s project 6 on the use and misuse of emotion, see here.