CDE project 9: putting the principles and actions into practice — part 1

- Written by

- The Commission on the Donor Experience

- Added

- April 29, 2017

Improve the (major) donor experience by…

1. Being really clear about what a major donor to your organisation actually is

When asked ‘how do you define a major donor to your organisation’ many fundraisers answer with a financial level, representing the level at which they have chosen to engage in a personal, one-to-one relationship rather than in a mass market, one-to-many relationship.

Many major UK charities set this level at £5,000. Some consider a single gift of £5,000 or more as major; whereas others consider cumulative gifts of £5,000 or more across a year as major. The basic approach is similar: major donors are defined by their current value to the organisation, commonly £5,000.

A second way of defining a major donor is a donor who has the potential to make a gift that will have a significant impact on the work of the organisation. This is used in the Code of Fundraising Practice.[13] It moves beyond current giving to potential giving. For many organisations, a gift that will have a significant impact on the work of the organisation will be much larger than the threshold level for their major donor programme. For small community organisations, a transformational gift might be a few thousands; for large international organisations, a transformational gift might be 7 figures—or more. In the project, the term major donors incorporates this range.

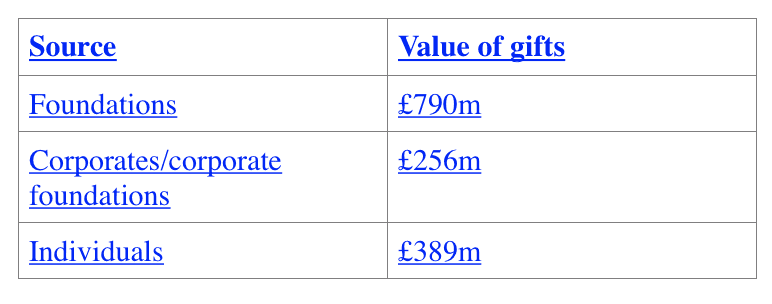

Often, major donors are thought of as individuals, but as the 2015 Coutts Million Dollar Donors Report for the UK [14] demonstrates, that is not the whole picture. The report provides a review of 7 figure gifts, and reported 298 gifts of £1m or more worth a total of £1.56b for 2014. The source of £1m/+ gifts is shown in the table below:

This highlights that foundations are the philanthropic vehicles for both individuals and companies. At the top of the donor pyramid, there is less distinction between individual, corporate and foundation giving. Many of the best practices found in managing major donor relationships are relevant to foundation and some corporate donors. This point is made by a number of authors in blogs and articles.[15]

The point is made strongly by Richard Perry and Jeff Schreifels of The Veritus Group (a USA major donor consulting agency) in a blog [16] on the subject. But perhaps the proof is the voice of the donor in a comment by Canadian, Rob Tonus:

‘Having managed a foundation for four years, I can attest to that . . . Charity staff and volunteers who approached me with respect and asked my opinion BEFORE submitting their proposals were more likely to be considered as good partners when projects were being reviewed by the Funding Committee. Those who thanked me whether they got their funding or not were more likely to be looked on favourably when they submitted their next proposal. And those who invited me to their celebration events, even if I couldn’t make it due to distance (I was responsible for providing funding throughout the whole province of Ontario) increased their chances of being looked on favourably when they asked for funding again.’

Rob Tonus [17]

A potential third way of defining a major gift is from the perspective of the donor: as a gift that is personally significant to the donor. This definition has an advantage in that it shifts thinking: major donors are those who are making an extraordinary commitment, for them, to a cause and organisation. However, it is also challenging practically:

- a personally significant gift of, say, £1,000 does not get recognised by an organisation because its major donor financial level is £5,000.

- the same organisation receives a gift of £10,000. This is treated as a major gift because the organisation’s major donor financial level is £5,000. The £10,000 gift is actually a small gift from a wealthy individual who is actually indicating they are not particularly interested in this cause or organisation. So someone who is not a major donor is treated as one.

This dilemma is one reason why all fundraisers should have a ‘major donor’ mindset: noticing and responding personally to a major gift even if it does not qualify for the organisation’s major donor programme will significantly enhance the donor experience.

Lastly, for many organisations a ‘major donor’ may not be a financial supporter. Rather, they might be an ‘influencer’: an individual who has or has the potential to have the ability to make a significant impact on the work of the organisation, perhaps through their contacts or connections or through their knowledge or expertise. For example, many organisations have high profile or celebrity supporters who may not be financial major donors, but who are committed to supporting the organisation by helping attract and engage new supporters. Similarly, many organisations have individuals who support their work by taking advocacy messages to particular audiences because of their connections and/or reach. These individuals are often managed by the organisation as ‘major donors’ because they make a significant contribution to the mission.

This discussion of the definition of major donors highlights two principles fundamental to the donor experience.

First, defining a ‘major donor’ is messy. Fundraisers need to carefully define what a major donor is in their organisation’s unique circumstances, taking into account:

- potential as well as current giving.

- whether to include foundation and/or corporate gifts, because at the top of the donor pyramid the distinctions are fine.

- why donors give to you, and how important the gifts to your organisation are to the donor.

- non-financial contributions that have significant impact, often through an individual’s contacts and connections.

Having done this, it is likely that a major donor programme will include a wide range of financial levels—perhaps from £5,000 to 7 figure gifts and beyond—and also non-financial support. Given this, there is a danger of confusion about the extent to which you can and should provide a completely individual and personal experience. To avoid this and to make sure that you align external donor and internal organisation expectations, you will need to create formal involvement, recognition and stewardship approaches tiered to different levels of financial and non-financial contribution.

The second principle is that organisations will improve the donor experience by applying major donor fundraising principles and techniques—primarily personal, one-to-one relationship management—to donors who give at levels below the major donor level. A key challenge is how to do this—and remain cost-effective. While this question is not addressed specifically in this project, I believe major donor fundraisers have a strategic role to play in answering it alongside their individual giving colleagues. While this sounds simple, too often there is too little real interaction between fundraisers in different disciplines to answer a question like this.

----------------------

[15] As one example see http://brightspotfundraising.co.uk/treating-trusts-as-major-donors/ for a blog by Rob Woods about how Lucy Sargent and James Holland of Marie Curie Cancer Care increased the trust income from £1m per year to £3.5m per year in four years by applying major donor fundraising techniques to trust and foundation relationships.

[16] See Veritus group

[17] See comments at the end of http://veritusgroup.com/treat-...